The Transmission of Buddhist Iconography and Artistic Styles around the Yellow Sea Circuit in the Sixth Century: Pensive Bodhisattva Images from Hebei, Shandong, and Korea

![]() Li-kuei Chien

Li-kuei Chien

When Buddhism reached the Korean peninsula and took root there between the fourth and sixth centuries, both China and the Korean peninsula were in a state of division. Regional powers competed against each other and waged wars for dominance on both sides of the Yellow Sea, making the political and cultural history of this period exceptionally complex. Korean rulers sought alliances with the powerful states to their west, and the transmission of Buddhist culture was accelerated along with these diplomatic exchanges.[1] Despite the rapid development of Buddhism on the Korean peninsula, the history of interaction between Korea and China remains a challenging topic because relevant textual documents from this period are scarce.[2]

Modern archaeological and art history research compensates for the lack of written records in this field.[3] Our understanding of the development of sixth-century Korean Buddhism and Buddhist art and their relationship with the outside world are largely based on material evidence such as stylistic and iconographic analysis of extant Buddhist sculptures, examination of the remains of monastic sites, and scrutiny of Buddhist motifs in tomb murals and objects.

These types of evidence suggest that although Buddhist emissaries reached Koguryǒ and Paekche in the late fourth century, the scale of Buddhist material culture remained limited for some time afterwards and was mainly associated with the royal courts. Early examples of Buddhist art include a small gilt bronze figure of a seated Buddha dated to the fifth century (found in the territory of Paekche but possibly produced elsewhere) and a painted mural of a seated Buddha in a late-fifth-century Koguryǒ tomb.[4] Production of Buddhist images increased during the sixth century and expanded to Silla, which developed closer connections to China after its consolidation of territorial conquests on the Yellow Sea coast in 553.[5] Scholars have tentatively proposed specifically northern or southern Chinese origins for certain stylistic features found in numerous individual Korean Buddhist statues from the sixth century, such as facial features, ornamentation, clothing, and drapery.[6] However, analysis of such stylistic features is made more challenging by uncertainties surrounding the geographical origins of many Korean statues and by the scarcity of surviving Buddhist sculptures from China’s southern dynasties.

Many questions about how Buddhist artistic styles were transmitted to the Korean peninsula thus remain unanswered. In particular, it is unclear which of the distinctive regional Chinese traditions provided the most important sources of inspiration for Buddhist artisans working on the peninsula. By identifying the characteristics specific to certain locales, we can see how these places related to each other as a region, transcending geographic and linguistic barriers to share similar Buddhist iconography and art across the Yellow Sea.

This article presents an iconographic and stylistic analysis of the pensive bodhisattva images popular in Hebei, Shandong, and the Korean peninsula from the sixth to the early seventh century. The pensive bodhisattva image was widely reproduced in north-east Asia from the sixth to the eighth century, with more than a hundred stone sculptures in the round discovered in Hebei, about fifteen in Shandong, and in Korea and Japan about thirty bronze statues each. Scholars have published extensively on this subject since the beginning of the twentieth century.[7] However, fundamental questions, including the sources of the iconography, the exemplars that provided artistic inspiration, the provenance of the extant works, and the religious meanings they carried remain hotly contested.

Over the past twenty years, a wealth of material has become available that sheds light on the relationship between Chinese and Korean pensive images. Following the rapid economic development of China during the 1990s, discoveries of ancient hoards during urban construction, new cultural policies to encourage the establishment and refurbishment of museums to display materials from old and new excavations, and the publication of existing materials have together enabled scholars to gain wider access to first-hand data for analysis and comparison.[8]

The postures of the pensive images from Hebei and Shandong are similar overall. The bodhisattva is portrayed seated with one leg pendent and the other folded laterally with the ankle resting on the knee of the pendent leg. One of his hands supports his head or has fingers pointing towards his cheek or temple, as if the figure is absorbed in contemplation (Fig. 1a). However, Hebei and Shandong pensive sculptures differ in material, artistic vocabulary, and iconographic arrangement. Hebei sculptures are mainly white marble while Shandong are grey limestone. The residual pigments on the surface of the stones show that both Hebei and Shandong sculptures were originally coloured. More exquisite works had a layer of white plaster applied before the addition of pigments, in order to make the colours more vivid. Nevertheless, the white marble base material of Hebei sculptures would still have made them appear more dazzling than Shandong sculptures to their original viewers in the sixth century.

Rear view of the pensive statue shown in Figure 1a. Courtesy of the Qingzhou Municipal Museum.

Most Korean pensive statues are made of bronze, requiring a different set of crafting techniques from the Chinese stone works. Despite this difference, we can still conduct stylistic comparisons to explore which formal features the Korean artisans learned from their Chinese counterparts. Although the pensive images on either side of the Yellow Sea show formal connections with each other, the thirty extant pensive images from Korea are each unique, without obvious stylistic similarities to one another. Scholars have proposed stylistic analyses to determine the respective provenances of these works and have come to divergent conclusions.[9] Yet despite continuing disputes over details, art historians generally agree that the majority of extant Korean pensive images from the sixth and early seventh centuries came from Paekche and Silla.[10]

After the new archaeological material became available, Ōnishi Shūya 大西修也 was the first scholar to discuss the iconographic connections between Shandong and Korean pensive bodhisattva images.[11] He proposed that one particular pensive statue from the Longxing Temple 龍興寺, Qingzhou 青州 (Figs 1a, 1b, 1c), was the prototype for a group of Korean pensive images sharing a distinctive way of arranging the ring and sash ornaments suspended from the bodhisattva’s waist. Ōnishi proposed on the basis of indirect evidence that this group of statues were produced in Silla; however, this argument rests on shaky foundations, since the provenances of the Korean pieces are unknown.

By broadening the scope of investigation through an examination of pensive sculptures from various sites around the Yellow Sea circuit, I argue that Korean pensive bodhisattva images show some iconographic connections with works from Shandong, while their overall style is closer to those from Hebei. Building on Ōnishi’s work, I first show that the ring and sash ornament, common in Shandong but rare in Hebei, was a common ornamental element in Shandong Buddhist art, and I argue that the appearance of this ornament on the Korean peninsula reflects iconographic influences from Shandong. However, I depart from Ōnishi’s conclusion based on the profound stylistic parallels between pensive images from Hebei and Korea. Finally, I argue that although textual records suggest that Silla and Paekche had stronger diplomatic relationships with southern China than northern China, material evidence suggests that Paekche and Silla had strong ties with northern China as well. This evidence suggests a need to reassess the history of cultural interactions in the Yellow Sea region during the sixth century, giving greater significance to the relationships between the southern Korean peninsula and north-east China.

Common Iconographic Elements in Shandong and Korea: Ring and Sash

Pensive bodhisattva statues have been unearthed in many places in Shandong that are concentrated on the coastal areas to the east of Mount Tai 泰山, including Zhucheng 諸城, Linqu 臨朐, Qingzhou, Boxing 博興, Huimin 惠民, and Wudi 無棣 (see Map 1).[12] One particular statue excavated from the Longxing Temple in Qingzhou has become extremely well known because of its fine condition, and has appeared in most major exhibitions and catalogues of Qingzhou sculptures around the world (Figs 1a, 1b, 1c).[13] This statue shows the bodhisattva sitting on an hourglass-shaped stool (Chin. quanti 筌蹄).[14] In the lower section of the stool, a carved dragon holds a lotus flower in its mouth, supporting the deity’s foot. The drapery of the bodhisattva’s skirt is depicted closely clinging to his legs, showing their contours and the shape of the stool.

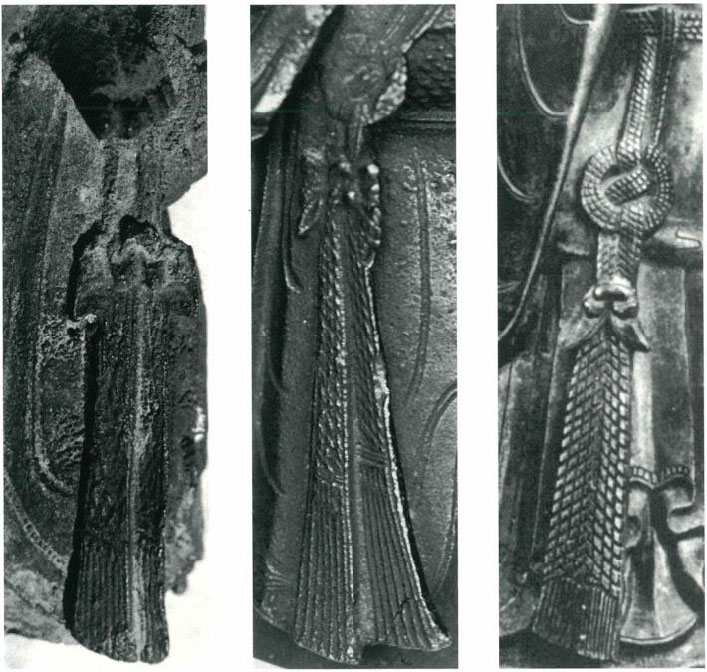

Ōnishi drew attention to a distinctive pair of ornaments worn by the bodhisattva composed of a ring and sash on either side of the bodhisattva’s hips. The rings are shown tied to two separate sashes — one to fix the ring to the waist and the other tucked between the seat and the buttocks of the pensive image before draping down over the side of the stool (Fig. 1c).[15] Ōnishi compared the arrangement of the rings and sashes between the Qingzhou example and those images believed to come from each of the three Korean kingdoms, finding that pensive statues believed to come from Silla have similar designs to that of the Qingzhou statue (Fig. 2), whereas pensive statues believed to come from Paekche have the ring tied to only one piece of sash that drapes down directly from the waist (Fig. 3). Based on records in the Suishu liyizhi 隋書禮儀志, Ōnishi further proposed that the ring and sash represented yuhuan 玉環 and shou 綬, elements of the formal ritual attire for princes in the southern dynasties and the Sui. It was out of admiration for the courtly attire of high-ranking royalty that the creators of the pensive statues in Qingzhou and on the Korean peninsula adopted this particular decorative scheme for their own creations.[16]

Illustration by Ōnishi Shūya to explain how the ring and sash ornament is arranged in ‘Silla’ pensive images. From Ōnishi, ‘The Monastery Kōryūji’s “Crowned Maitreya” and the Stone Pensive Bodhisattva Excavated at Longxingsi,’ in eds Washizuka Hiromitsu, Park Youngbok, and Kang Woo-Bang, Transmitting the Forms of Divinity: Early Buddhist Art from Korea and Japan (New York: Japan Society, 2003), Fig. 9.

Besides the Qingzhou pensive statue discussed above, two other pensive statues from Linqu show extant traces of the ring and sash ornaments. Both statues have the rings tied to two separate sashes, but they differ in the positioning of the rings and sashes on the body. The statue shown in Figs 4a, 4b, and 4c has the ring carved on the back of the body near the hip. The sashes are carved in elegant flowing contours along the body and the stool, conveying the lightness and softness of the fabric; the lower segments of the sashes are tied into elaborate knots. In the other pensive statue, the rings and sashes are carved on the sides of the body (Figs 5b, 5c), with the lower segments of the sashes stretched to the thighs and placed under the elbows before draping down naturally.

The three pensive statues from Shandong (one from Qingzhou and two from Linqu) have distinct arrangements of the rings and sashes without following any formulaic styles, showing that the Shandong Buddhist artisans were confident in their skill to experiment with various designs.

A survey of other Shandong bodhisattva statues makes it clear that the ring and sash ornament was not exclusive to the pensive statue but, rather, was common in Shandong Buddhist art, depicted in a variety of designs. In most cases in Qingzhou, the ring is tied to two separated sashes — one to the waist and the other draping down from the ring (Fig. 6). These ornaments have sophisticated designs: some rings are adorned with a pearl-roundel pattern and the lower sash is tied in an elegant bow (Fig. 6). Some rings are fixed to the central set of jewels (Fig. 7), some have sashes passing through them (Fig. 8), and some are embellished with one knot above and another knot below. In some cases, the sashes have elaborate carvings in the shape of pearls and are embellished with gold leaf (Fig. 9).

Illustration shown by Ōnishi Shūya to explain how the ring and sash ornament is arranged in ‘Paekche’ pensive images. From Ōnishi, ‘Stone Pensive Bodhisattva ..,’ Fig. 13.

Possibly drawing inspiration from their visual knowledge of aristocratic attire, sixth-century artisans in Zhucheng painstakingly delineated the ying-luo zhubao 瓔珞珠寶 described in scriptures, as if their efforts could transform the stone bodhisattvas into efficacious heavenly beings. In Zhucheng, many bodhisattva statues have rings and sashes similar to those found in Qingzhou, but with even greater complexity and variety.[17] The work shown in Fig. 10 has two separate sashes passing through the ring with precious pendants decorating the lower segments of the sash. The ring on the sculpture shown in Fig. 11 has a sophisticated knot in the circle outside of its left leg. Bodhisattva statues from Linqu, just 30km from Qingzhou, are also lavishly embellished; some even have double ring designs (Fig. 12). In Jinan, a sculpture has sashes twisted within the ring to add more detail (Fig. 13). Similar accessories can also be seen on bodhisattva sculptures from Boxing, now in the Boxing Municipal Museum.

The above examples illustrate how sixth-century Buddhist artisans in Shandong emphasised decorative effects. Their success relied largely on the fact that Shandong limestone has suitable hardness for fine carving and a dense texture for surface polishing. These qualities enabled the craftsmen to execute their carving techniques to capture the finest details, creating a sense of depth and producing a visual effect of luxury and extravagance. These qualities also allow us to observe decorative details 1500 years after their creation, even though the original colours have chipped and faded. Although Ōnishi cited textual evidence in support of his hypothesis that the ring and sash were modelled on southern court dress, it is more likely that the visual inspiration for the ring and sash ornament on bodhisattvas in Shandong came directly from Luoyang — the capital of the Northern Wei until 534. In the Binyang Middle Cave 賓陽中洞, an imperial chapel cut in the 510s at the Longmen cave temples near Luoyang, two attendant bodhisattvas have rings and sashes suspended from their waists (Figs 14, 15). Since wearing jades and sashes was a conventional mark of prestigious status, it is natural that the bodhisattva sculptures in the capital city were depicted in a similar way.[18]

The above examples illustrate the decorative characteristics of Shandong Buddhist art, with the ring and sash ornament as a distinctive part of this artistic practice. Korean artisans incorporated this ornamental aesthetic from Shandong in their own creation of pensive statues, such as Korean National Treasure number 83 (hereafter NT83; Figs 16a, 16b, 16c) and NT78 (Figs 17a, 17b). However, although this particular iconographic element suggests strong connections between the Buddhist art of Shandong and the Korean peninsula, the pensive statues from these two areas exhibit rather different overall artistic styles. The Korean statues employ a distinctive artistic vocabulary in the treatment of the volume and the proportion of the body, the form of the stools, and the folds in the drapery. As I argue below, the closest parallels for these stylistic features are to be found not in Shandong, but in Hebei.

Stylistic Connections between Hebei and Korea: Proportion and Volume of the Body, Form of the Stool, and Folds of Drapery

Proportion and volume of the body

The primary difference in the overall visual effects of the Shandong and Korean works is the proportion and volume of the bodhisattva’s body. Although Korean pensive images vary in body volume — some fuller and others more slender — they are in general well-proportioned, approximating more closely to the true proportions of the human body (NT83: Figs 16a, 16b, 16c; NT78: Figs 17a, 17b). The extant works from Shandong, by contrast, show greater stylisation in the relative sizes of the arms, legs, and torso. The Qingzhou statue shown in Figs 1a and 1b, for example, is slender in build, following the Eastern Wei (534–550) style, with a relatively flat upper torso, an oversized head, an elongated right arm, a stiff left arm, and thin legs. Another Qingzhou pensive statue (Fig. 18), shaped with a fuller body in the Northern Qi (550–577) style, has the left armpit awkwardly lower than the right. Both Shandong examples are less elegant and natural in capturing the proportions of the body than the Korean works.

Besides the appropriate proportion and volume of the body, Korean artisans also mastered the skill of expressing the curves of the torso, carefully defining the characteristics of the chest and the abdomen. The profile views of NT83 and NT78 show their well-built chests gently swelling out, clearly distinguishing the chest from the abdomen and the waist. In contrast, all the known Shandong works have a flat and simple curvature for the front of the torso.

The realistically depicted proportions, volume, and curves of the body in Korean pensive statues are closer to those of the Hebei counterparts. One exemplary Hebei statue in the Freer Gallery (Figs 19a, 19b) shows that the body is well-proportioned. Although the head is slightly on the large side, it conveys a sense of childlike innocence. To define the contour of the chest, Hebei craftsmen used lightly incised lines from the armpit to demarcate the chest from the arms and abdomen on the front of the torso. The visual effect of a muscular chest is thereby achieved, despite the lack of prominent swelling when viewed in profile. The techniques by which Hebei and Korean craftsmen manipulated the proportions, volume, and curves of the body to create a realistic body image are not found in extant Shandong pensive images.

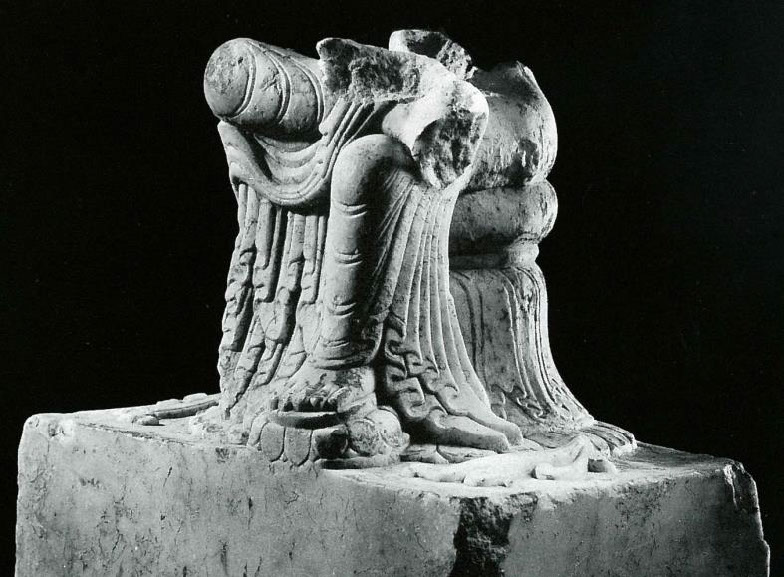

Stool

Another stylistic similarity between the Korean and Hebei pensive images is the design of the stool. The majority of pensive statues from Korea and Hebei show a bodhisattva sitting on a stool shaped like a bucket. A neck is formed near the top with the upper section much shorter than the lower (Figs 16c, 17b, 20). The stools are carved with flowing incised lines or in low relief to suggest that they are smoothly cloaked in fabric. In NT83, the fabric covering the stool elegantly extends to the floor and the folds on the stool are neat and continuous, creating a sense of grace and serenity. These features are almost identical to those in the fragmentary Hebei pensive image shown in Fig. 20. In another Korean work (Figs 21a, 21b, 21c), not only is the stool rendered in the same manner as those in NT83 and in the Hebei statue in Fig. 20, but a large lotus pedestal is also carved supporting the stool and a small lotus is added supporting the foot, in a manner resembling the Hebei statue.

The shape of the stools in Shandong statues is completely different from that in Hebei and Korean images, though the carvings and traces of the remaining pigments on the surface of the stools in Shandong pensive statues also suggest the craftsmen’s intention to represent a layer of fabric wrapping around the seat. Shandong pensive bodhisattvas usually sit on an hourglass-shaped stool (Figs 1b, 5b, 18) — a form believed to have come to China from Central Asia with the spread of Buddhism.[19]

Drapery

A third stylistic similarity between the Hebei and Korean pensive images can be seen in the folds of the skirt. Korean pensive statues generally have long skirts covering both the legs and the stool at the front. Close examination of the folds of the skirt reveals that the folds tend to concentrate in two areas: under the folded leg (Areas A, B in Figs 22, 23) and around the ankle of the pendent leg (Area C in Figs 22, 23). The set of horizontal curving lines beneath the folded leg (Area A) is a realistic depiction of the skirt getting bundled up and making the skirt shorter in appearance. Beneath the curving lines, another set of folds represent the hems of the skirt on the front of the body (Area B). The concentration of the skirt folds near the ankle of the pendent leg represents the rear portion of the skirt hanging down from the seat and almost touching the floor (Area C).

Ring and sash ornament on the right side of a standing bodhisattva statue. Qingzhou Municipal Museum.

Ring and sash ornament tied to the central set of jewels of a standing bodhisattva statue. Qingzhou Municipal Museum.

The execution of the skirt folds in the Korean pensive images by and large conveys a sense of naturalism, with some folds represented in a flattering fashion (NT78) and others in a more three-dimensional manner (NT83).[20] The skirt folds in Hebei pensive images exhibit the same tendency (Figs 19a, 20, 24, 25). The folds under the raised leg of Fig. 24 are intricately carved in a complex formulaic pattern, while those in Fig. 25 are more straightforwardly repetitive, but both display an intention to depict realistically the folding of the skirts. Through various concentrations of the folds, the skirts are made to appear shorter in the front and longer in the back, as they would normally be in a seated position.

The skirt folds in the Shandong pensive statues are expressed with a very different artistic vocabulary from the Korean and Hebei statues. The length of the skirt in the Shandong statues is usually shorter, reaching only the upper section of the raised leg (Figs 1a, 5a, 18). The skirt presents an overall flat impression, with simple folds and few layers. Allowing for obvious differences in the craftsmen’s training, techniques, and artistic tendency, the treatment of skirt folds and body volume suggest that Korean and Hebei artisans shared a similar pursuit of realistic expression in the overall style of the pensive image.

Finally, an exceptional pensive bodhisattva statue from the Mingdao Temple in Linqu (Figs 4a, 4b, 4c) reveals that craftsmen and patrons were aware of the existence of distinctive local styles and that they freely and selectively combined iconographic and stylistic elements. This statue has rings and sashes similar to the other Shandong statues, but the folds of skirt resemble the works from Hebei in style. Since this statue is made of limestone, typical of Shandong statues, it is safe to assume that it was made locally in Shandong. The curious stylistic and iconographic synthesis seen in this piece suggests that it could have been a Shandong attempt at imitating Hebei style, or perhaps a Hebei sojourning artisan’s effort, incorporating local iconography. The artisan’s creativity is further demonstrated by his inclusion of a form of stool rarely seen in either Shandong or Hebei. The stool is neither in the slender hourglass shape common in Shandong nor the bucket shape with short upper section and long lower section popular in Hebei. Rather, it is divided into two equal sections separated by a thick waist — a form possibly adopted from the pensive images in the Weizi Cave 魏字洞 and Putai Cave 普泰洞 at Longmen, cut in the 520s. This eclectic synthesis of iconographic and stylistic elements from different sources provides the closest parallels to the features of Korean pensive images among all currently known pensive images from China.

Ring and sash ornaments suspended from the right side of bodhisattvas’ waists. Shandong Museum.

Diplomatic and Buddhist Contacts across the Yellow Sea

The iconographic and stylistic similarities between Korean, Shandong, and Hebei pensive images can offer us new insights into the history of cultural exchange around the Yellow Sea circuit. The lack of textual records makes it difficult to ascertain the exact paths by which Buddhist visual culture reached the peninsula. However, available information and existing scholarship suggest several possibilities:

1) Shandong and Hebei merchants coming to Korea may have sold Buddhist items as merchandise or brought them as personal icons or amulets, following the historical pattern by which Buddhist visual culture had originally been transmitted to China from the Western Regions.[21]

2) Chinese monks may have brought Buddhist icons to Korea for evangelical purposes.

3) General population movements across the Yellow Sea may have allowed Chinese Buddhist artistic styles and iconography to enter Korea and to be synthesised with local indigenous aesthetics and techniques.[22]

4) Buddhist icons may also have been sent together with Chinese Buddhist artisans and painters as official gifts from Chinese to Korean courts as part of diplomatic exchanges. Events such as these created the environment in which Korean artisans and patrons imitated, reproduced, and reinterpreted Chinese pensive images.

Understanding which Chinese regions served as sources of inspiration for Buddhist artisans working on the Korean peninsula can provide clues as to which of the above modes of transmission were predominant. The majority of surviving Korean pensive statues are thought to come from Paekche and Silla, which were geographically closest to the Shandong peninsula in the north and to the coastal regions of the southern dynasties.[23] The shortest maritime route between Shandong and Paekche was only 300 kilometres, which could be crossed in a few days of sailing.[24] This geographic proximity was important for determining maritime trade routes, and it may also have enabled monastic and lay Korean travellers to become familiar with the characteristic features of Shandong Buddhist art. However, the influence of Hebei artistic traditions on Korean pensive bodhisattva statues suggests that mere geographic proximity was not the primary factor influencing the pathways by which Chinese artistic styles were transmitted to the Korean peninsula. After 534, Hebei was the location of the northern dynasties’ capital Ye 鄴 (modern-day Linzhang 臨漳). The stylistic similarities between Korean pensive bodhisattva statues and those of the region around the northern dynasties’ capital (rather than the geographically closer region of Shandong) suggest that the transmission of Buddhist artistic traditions to Korea was linked to diplomatic contacts between the northern dynasties and the courts of Paekche and Silla.

Sash twisted with the ring suspended from the right side of the bodhisattva’s waist. Shandong Museum.

Records in Chinese and Korean official histories suggest that during the fifth and early sixth centuries, Paekche and Silla maintained close relationships with the southern Chinese dynasties, while Koguryŏ had more regular contacts with the northern dynasties (Table 1).[25] Earlier scholars have pointed out two major reasons that contributed to such alliances. Geographically, Koguryŏ blocked Paekche’s and Silla’s overland paths and interfered with their sea routes to northern China. Therefore, when the two southern states wished to contact China, it was easier for them to reach the southern dynasties.[26] Moreover, Koguryŏ had established friendly relationships with China’s northern political powers, and Silla and Paekche therefore formed strategic alliances with China’s southern political entities in order to resist Koguryǒ.[27] Amicable political relationships were usually accompanied by fruitful cultural exchanges, and material evidence from Paekche and Silla reflects cultural influences from the southern dynasties.[28]

Table 1: Dates of contact between Chinese and Korean states

|

Northern China |

Southern China |

|

|

Koguryǒ |

435, 436, 437, 439, 462, 465, 466, 467, 468, 469, 470, 472, 473, 474, 475, 476, 477, 479, 484, 485, 486, 487, 488, 489, 490, 491, 492, 493, 494, 495, 498, 499 500, 501, 502, 504, 506, 507, 508, 509, 510, 512, 513, 514, 515, 517, 518, 519, 532, 534, 535, 536, 537, 538, 539, 540, 541, 542, 543, 544, 545, 546, 547, 548, 549, 550, 551, 555, 560, 564, 565, 573, 576 |

420, 423, 424, 436, 438, 439, 441, 443, 451, 453, 455, 458, 459, 461, 463, 480, 481 502, 508, 512, 517, 520, 521, 526, 527, 532, 534, 541, 548, 561, 562, 566, 568, 570, 571, 574, 585 |

|

Paekche |

472, 567, 570, 571, 572, 578, 581, 582, 589 |

406, 416, 420, 429, 430, 440, 443, 450, 457, 467, 471, 480, 484, 486, 490 502, 512, 521, 524, 534, 541, 549, 562, 567, 577, 584, 586 |

|

Silla |

564,565,572 |

521, 549, 565, 566, 567, 568, 570, 571, 578, 585, 589 |

Buddhist activities were an important element in Paekche and Silla’s diplomacy with the southern dynasties.[29] According to the Samguk sagi 三國史記, compiled in the twelfth century, Paekche’s embassy to the Liang in 541 asked for supplies of Buddhist scriptures and artisans (gongjiang 工匠) and painters (huashi 畫師).[30] In 549, the Liang sent diplomats to accompany a Silla monk returning to Silla with Buddhist relics.[31] In 565, the Chen court sent a diplomatic mission to Silla with Buddhist monks as members of the official embassy, bringing 1700 fascicles of Buddhist scriptures (jing 經) and treatises (lun 論) as national gifts.[32] Silla and Paekche monks usually chose southern China as a destination for studying Buddhism.[33] These historical records indicate that Silla and Paekche had strong Buddhist ties with southern China and that Buddhist gift-giving was an accepted component of diplomatic exchanges.

Ring and sash ornament carved on a bodhisattva on the west wall of the Binyang Middle Cave, Longmen.

Political contacts between Koguryŏ and the northern dynasties also included similar Buddhist activities. The Chinese hagiography Xu gaosen zhuan 續高僧傳, compiled in the seventh century, recounts that in 576, Koguryŏ’s grand councillor-in-chief (da chengxiang 大丞相) sent monks to study Buddhist doctrines and history at the Northern Qi capital Ye.[34] The embassy met with the grand controller-in-chief (da tong 大統) Fashang 法上 — the highest Buddhist official of the Northern Qi — to receive instruction on Buddhism and Buddhist history.[35] This Buddhist engagement at the highest level between the two countries very likely led to national gifts from the Northern Qi court to Koguryǒ such as Buddhist scriptures and icons that may later have come to influence the development of Korean Buddhist art.

The connections between Koguryǒ and Shandong Buddhist art have been discussed extensively by earlier art historians. Dong-seok Kwak has pointed out the similarities in the design of mandorlas in Shandong and a Koguryǒ Buddhist bronze.[36] Soyoung Lee and Denise Patry Leidy have also discussed the likeness in physique and the rendering of the flowing folds of the shawls and garments between the same Shandong and Koguryǒ works.[37] John Jorgensen has raised the possibility that the internal layout of Koguryǒ stupas was based on a model in the Shentong Monastery (Shentongsi 神通寺) in Shandong.[38]

Yet although the textual sources and the material evidence discussed above suggest that Koguryǒ interacted primarily with northern China and Paekche and Silla with southern China, recent scholarship has suggested a more complex pattern of relationships, especially during the second half of the sixth century. Jonathan Best has pointed out that although Buddhist decorative patterns with influences from the Liang such as lotus blossoms were popular throughout the sixth century, Buddhist sculptural styles shifted in accordance with Paekche’s changes in foreign policy, from resembling southern Chinese styles to the northern Chinese styles.[39] Tanabe Saburōsuke has mentioned the resemblance between Paekche and Shandong Buddha sculptures.[40] Songeun Choe has discussed the general similarities between Silla pensive statues and those from northern China, pointing out that they have a bare upper body, wear a thin necklace, and have drapery flowing from their waist.[41] Taken together, these observations imply extensive cultural contacts between China’s northern dynasties and the southern kingdoms on the Korean peninsula. The similarities between Hebei and Korean pensive bodhisattva statues discussed in the previous section not only provide additional evidence for these contacts, but suggest the further conclusion that they were directly linked to diplomatic exchanges between northern dynasties and southern Korean courts. Meanwhile, the iconographic elements of Korean pensive bodhisattva statues adopted from Shandong prototypes demonstrate that although the artisans who produced the Korean pensive statues were working primarily in the tradition of the Hebei style, their sources of inspiration were not restricted to Hebei alone, but also incorporated distinctive features of geographically closer regions of China such as Shandong.

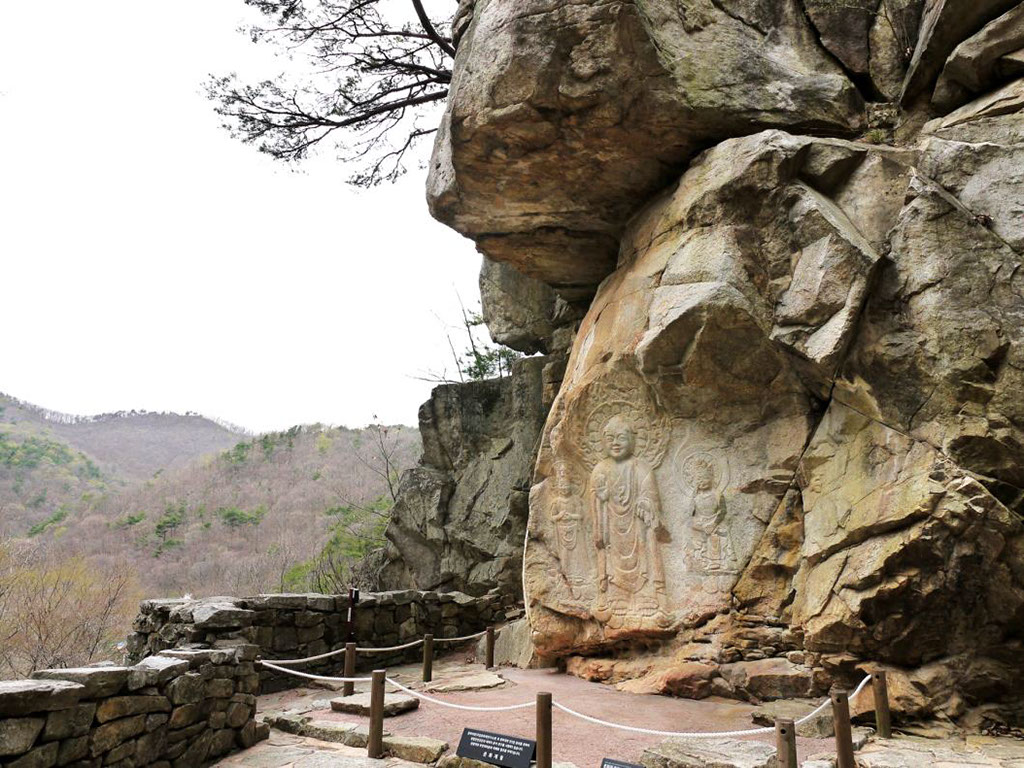

Pensive bodhisattva statue, NT83, frontal, side, and rear view. Courtesy of the National Museum of Korea.

This complex network of connections between Buddhist artistic production in Hebei, Shandong, and the Korean peninsula was not limited to the pensive bodhisattva statues. A similar process of integration of multiple Chinese regional traditions can be seen in the cliff carving in Sǒsan 瑞山, in the territory of ancient Paekche, slightly inland from the Tae’an 泰安 peninsula protruding into the Yellow Sea.[42] This carving has a central Buddha figure, probably intended to represent Amitābha, flanked by an Avalokitêśvara on the viewer’s left and a pensive bodhisattva on the viewer’s right (Fig. 27). The cliff faces east, so that worshippers viewing the images would be facing west — the direction of Amitābha’s Western Paradise. This combination of Avalokitêśvara and the pensive bodhisattva was a popular iconographic practice in sixth-century Hebei with many examples discovered at the site of the Northern Qi capital Ye.[43] Many of these Hebei images show evidence that their patrons aspired to rebirth in Amitābha’s Western Paradise, and it is possible that the depiction of the pensive bodhisattva beside Amitābha on the Sǒsan cliff carving was directly inspired by religious traditions from Hebei. On the other hand, since cliff carving of Buddhist icons and scriptures was a popular practice characteristic of sixth-century Shandong, the existence of this triad on a cliff face strongly suggests a direct connection with Shandong.[44] Like the Korean pensive bodhisattva statues, this cliff carving shows that Korean artisans integrated iconographic and stylistic features from different regions of northern China to produce a distinctive artistic style of their own.

Pensive bodhisattva statue frontal and side views, NT78, Courtesy of the National Museum of Korea.

Pensive statue from the Longxing Temple, Qingzhou. Qingzhou Municipal Museum. From Kim Seunghee, Kim Haewon, Jeong Myounghee, ed., Masterpieces of Early Buddhist Sculpture, 100BCE–700CE (Seoul: National Museum of Korea, 2015), p.254.

Pensive statue (front and side views) in Hebei style. Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.: Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1911.411.

Pensive statue from the Xiude Temple, Quyang. Palace Museum, Beijing. Matsubara Saburō, Chūgoku Bukkyō chōkoku shiron 中国仏教彫刻史論, Vol.1 (Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan, 1995), pl.268a.

Conclusion

The geographic distribution, artistic styles, and iconography of extant pensive images around the Yellow Sea circuit are consistent with the increasing tendency towards closer cultural interactions between the southern Korean kingdoms of Silla and Paekche and the northern Chinese dynasties over the course of the sixth century.[45] The production of independent pensive bodhisattva images — a Buddhist phenomenon unique to Hebei and Shandong in China that reached its climax in the mid-sixth century — inspired the production of similar images as the most prominent bodhisattva icon in Paekche and Silla just a few decades later. However, because of gaps in the textual record, we are as yet unable to answer questions such as the route by which the pensive bodhisattva reached the Korean peninsula, the time and context of this transmission, or the social identities of its earliest sponsors. Iconographic and stylistic analyses provide the best form of evidence available for understanding the historical connections of different groups of artisans across time and space.

Pensive statue (frontal, rear and side views) believed to be from Chungcheong-namdo in the territory of ancient Paekche. Tokyo National Museum.

Skirt folds of NT83 (Figures 16a, 16b, and 16c). Adapted from the National Museum of Korea Collection Database.

Pensive bodhisattva, dated 545, from the Xiude Temple, Quyang, Hebei. Courtesy of The Palace Museum. Photograph by Zhao Shan 趙.

Nevertheless, the iconographic and stylistic analysis presented here points towards the conclusion that the most iconic image of Silla and Paekche Buddhist art was inspired by contacts with north-east China. Moreover, it shows that the Korean artisans owed their inspiration not to a single source in northern China but to multiple distinctive regional Chinese traditions, integrating the Hebei artistic traditions with iconographic elements from Shandong art to arrive at a unique representational and iconographic style.

In contrast to previous scholarship that presumed a special relationship between the Buddhist art of the Korean peninsula and that of Shandong, I have proposed that the Korean pensive bodhisattva statues bear a more profound relationship to those from Hebei. The refined handling of the stylistic features that Korean pensive statues share with those of Hebei — especially the proportions and volume of the body and the detailed treatment of the drapery — are most likely to have been transmitted through direct personal relationships among artisans, perhaps through the training of Paekche and Silla artisans in Hebei or through the migration of Hebei artisans to Paekche and Silla. By contrast, the features shared between pensive statues from Korea and Shandong — the sash and ring — are relatively superficial design elements that could have been incorporated through imitation after a brief visual encounter.

This conclusion suggests that it may be necessary to reconsider the emphasis that recent scholarship has given to the role of Shandong in the transmission of Buddhist artistic styles to the Korean peninsula, and to explore more thoroughly the roles of other local northern Chinese artistic traditions. The details of my argument depend on stylistic features that are unique to the pensive bodhisattva and show clear differences between images produced in Hebei and Shandong. It remains to be seen whether a comparative analysis of other types of Buddhist icon might suggest different geographic patterns of transmission and imitation. Nevertheless, the pensive images themselves stand as a testament both to the complexity of sixth-century artistic exchanges around the Yellow Sea and to the ingenuity of the artisans who drew on multiple regional traditions in order to create them.

I am grateful to Mr Gong Dejie 宮德杰 and Ms Yi Tongjuan 衣同娟, the former and present Directors of Linqu County Museum, who welcomed research on the museum’s collection and granted me permission to study and photograph the sculptures discussed in this paper. I acknowledge Kim Minku 金玟球 for his discussion on secondary scholarship and for informing me of the latest archaeological discoveries in Korea. I thank Lee Yu-min 李玉珉 for her advice on the title of this paper. The work in this paper was substantially supported by a grant from the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (Project No. PolyU 559713).

Li-kuei Chien

Independent scholar

chien.likuei@gmail.com

EAST ASIAN HISTORY 43 (2019)

1 Jonathan Best discussed how the Chinese cultural influence in Paekche grew along with the political exchanges between the two countries in his ‘Diplomatic and Cultural Contacts Between Paekche and China,’ Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 42.2 (1982): 443–501. For a more comprehensive study of Paekche history, see Jonathan Best, A History of the Early Korean Kingdom of Paekche, Together with an Annotated Translation of the Paekche Annals of the Samguk sagi (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 2006).

2 For brief discussions of the uses of these texts in the study of early Korean history, see Rhi Juhyung, ‘Seeing Maitreya: Aspiration and Vision in an Image from Early Eighth-Century Silla,’ in ed. Youn-mi Kim, New Perspectives on Early Korean Art: From Silla to Koryŏ (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013), p.73; Youn-mi Kim, ‘(Dis)assembling the National Canon: Seventh-Century ‘Esoteric’ Buddhist Ritual, the Samguk yusa, and Sach’ŏnwang-sa,’ in ed. Youn-Mi Kim, New Perspectives on Early Korean Art: From Silla to Koryŏ (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013), pp.123–24.

3 Kwon Oh Young indicated that in the study of the early history of Korea, archaeological data plays a more significant role than written records in his ‘The Influence of Recent Archaeological Discoveries on the Research of Paekche History,’ in ed. Mark E. Byington, Early Korea: Reconsidering Early Korean History Through Archaeology (Cambridge, MA: Korean Institute, Harvard University, 2008), p.65. In the study of ancient archipelagic-peninsular relations, William Wayne Farris pointed out that written sources alone cannot solve all the puzzles. One has to rely on archaeology, which in turn makes the revision of the historical view delineated by textual records possible. See William Wayne Farris, ‘Ancient Japan’s Korean Connection,’ Korean studies 20 (1996): 1–22.

4 Kim Lena, ‘Tradition and Transformation in Korean Buddhist Sculpture,’ in ed. Judith Smith, Arts of Korea (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998), pp.253–54.

5 Jonathan W. Best, ‘The Transmission and Transformation of Early Buddhist Culture in Korea and Japan,’ in eds Washizuka Hiromitsu, Park Youngbok, and Kang Woo-Bang, Transmitting the Forms of Divinity: Early Buddhist Art from Korea and Japan (New York: Japan Society, 2003), p.22.

6 For a useful survey of the artistic evidence, see Kim Lena, Buddhist Sculpture of Korea (Elizabeth: The Korea Foundation, 2007).

7 Mizuno Seiichi 水野清一, ‘Hanka shiyuizō ni tsuite’ 半跏思惟像について (1940), in Chūgoku no bukkyō bijutsu 中國の佛教美術 (Tokyo: Heibonsha, 1968), pp.243–250; Sasaguchi Rei, ‘The Image of the Contemplative Bodhisattva in Chinese Buddhist Sculpture of the Sixth Century’ (PhD diss., Harvard University, 1975); Tamura Enchō 田村圓澄 and Hwang Su-yǒng 黃壽永, eds Hanka shiyuizō no kenkyū 半跏思惟像の研究 (Tokyo: Yoshikawa kōbunkan, 1985); Lee Yu-min 李玉珉, ‘Banjia siwei xiang zaitan’ 半跏思惟像再探, National Palace Museum Research Quarterly 3.3 (1986): 41–55; Denise Patry Leidy, ‘The Ssu-Wei Figure in Sixth-Century A.D. Chinese Buddhist Sculpture,’ Archives of Asian Art 43 (1990): 21–37; Junghee Lee, ‘The Origins and Development of the Pensive Bodhisattva Images of Asia,’ Artibus Asiae 53.3/4 (1993): 311–41; Eileen Hsiang-ling Hsu, ‘Visualization Meditation and the Siwei Icon in Chinese Buddhist Sculpture,’ Artibus Asiae 62.1 (2002): 5–32; Katherine Tsiang, ‘Resolve to Become a Buddha (Chengfo): Changing Aspiration and Imagery in Sixth-Century Chinese Buddhism,’ Early Medieval China (2008): 115–169.

8 The archaeological findings from the Longxing Temple 龍興寺 in Qingzhou 青州, Shandong in 1996 made its debut exhibition in 1999 in Beijing. See Su Bai 宿白 et al., Shengshi chongguang: Shandong Qingzhou Longxingsi chutu fojiao shike zaoxiang jingpin 盛世重光:山東青州龍興寺出土佛教石刻造像精品 (Beijing: National Museum of Chinese History, Beijing Chinasight Fine Art Co., Qingzhou Municipal Museum, 1999). The inscriptions discovered from the Xiude Temple 修德寺 in Quyang 曲陽, Hebei in 1958 and 1959 were published in their entirety in 2005, including 47 inscriptions on the pensive images and many more pictures. See Feng Hejun 馮賀軍, Quyang baishi zaoxiang yanjiu 曲陽白石造像研究 (Beijing: Zijincheng, 2005). The Buddhist Statues Exhibition Gallery within the Beijing Palace Museum was completed and open to public in 2015. In 2013, Hebei Museum was reopened after eight years of renovation and dedicated the Quyang Stone Sculpture Exhibition Hall to displaying the sculptures discovered from the Xiude Temple. Yecheng Museum 鄴城博物館 and Linzhang Buddhist Statues Museum 臨漳佛教造像博物館 were opened in 2013 and 2015 respectively, exhibiting more than a hundred statues excavated from Linzhang in 2012. All of the abovementioned collections include pensive images on display.

9 For example, Youngsook Park and Roderick Whitfield believe Korean National Treasure number 78 hereafter NT78] came from Silla or Paekche, but Kang Woobang attributes it to Koguryŏ, based on his analysis of the artistic style and craftsmanship of the work. See Youngsook Park and Roderick Whitfield, Handbook of Korean Art: Buddhist Sculpture (Seoul: Yekyong Publishing Co., 2002), p.122; Kang Woobang, ‘Gilt-Bronze Pensive Image with Sun and Moon Crown: Reinterpretation of Gorguyeo, Baekje and Silla Buddhist Sculptures of the 6th Century and the Japanese Tori Style,’ in ed. Kang Woobang, Korean Buddhist Sculpture: Art and Truth (Chicago: Art Media Resources; Gangneung: Youl-hwadang, 2005), pp.31–68.

10 Several pensive statues that remained at their original sites until modern times are located in the territories of ancient Paekche and Silla, including the cliff carving in Sŏsan (Fig. 24) and the stone sculpture at Bongwha 奉化 (now in Kyŏngbuk University Museum). A recent discovery of a bronze pensive statue from Kangwǒn-do 江原道, ancient Silla, is the only pensive statue unearthed with scientific archaeological methods. However, the statue is rather small at 15cm, and thus easily portable. The place of production is therefore uncertain. See ‘Excavated in Korea for the First Time in the Area of Yeongwol,’ Naver, <http://news.naver.com/main/read.nhn?mode=LSD&mid=sec&oid=016&aid=0001374701&sid1=001>.

11 Ōnishi Shūya 大西修也, ‘Santōshō Seishū shutsudo sekizō hankazō no imi suru mono’ 山東省青州出土石造半跏像の意味するもの, Ars Buddhica 248 (January 2000): 53–67. Ōnishi Shūya, ‘The Monastery Kōryūji’s “Crowned Maitreya” and the Stone Pensive Bodhisattva Excavated at Longxingsi,’ in eds Washizuka Hiromitsu, Park Youngbok and Kang Woo-Bang, Transmitting the Forms of Divinity: Early Buddhist Art from Korea and Japan (New York: Japan Society, 2003), pp.54–65.

12 No pensive statue is mentioned in the archaeological reports, but there is one on display in the Zhucheng Municipal Museum. See Zhuchengshi Bowuguan 諸城市博物館, ‘Shandong Zhucheng faxian beichao zaoxiang’ 山東諸城發現北朝造像, Kaogu 8 (1990): 717–26, pls II–IV. Linqu County Museum 臨朐縣博物館, ‘Shandong Linqu Mingdaosi shelita digong fojiao zaoxiang qingli jianbao’ 山東臨朐明道寺舍利塔地宮佛教造像清理簡報, Wenwu 9 (2002): 64–83; Shandong sheng Qingzhoushi bowuguan 山東省青州市博物館, ‘Qingzhou Longxingsi fojiao zaoxiangjiaocang qingli jianbao’ 青州龍興寺佛教造像窖藏清理簡報, Wenwu 2 (1998): 4–15; Lukas Nickel, Return of the Buddha (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2002), pp.156–57; Chang Xuzheng 常敘政 and Li Shaonan 李少南, ‘Shandong sheng Boxing xian chutu yipi beichao zaoxiang’ 山東省博興縣出土一批北朝造像, Wenwu 7 (1983): 38–44; Li Shaonan 李少南, ‘Shandong sheng Boxing chutu baiyujian Beiwei zhi Suidai tingzaoxiang’ 山東博興出土百餘件北魏至隋代銅造像, Wenwu 5 (1984): 21–31; Ding Mingyi 丁明夷, ‘Tan Shandong Boxing chutu de tong fo zaoxiang’ 談山東博興出土的銅佛造像, Wenwu 5 (1984): 32–43; Shandong sheng Boxing xian wenwu guanlisuo 山東省博興縣文物管理所, ‘Shandong Boxing Longhuasi yizhi diaocha jianbao’ 山東博興龍華寺遺址調查簡報, Kaogu 9 (1986): 813–21; Huiminxian wenwu shiye guanlichu 惠民縣文物事業管理處, ‘Shandong Huimin chutu yipi Beichao fo zaoxiang’ 山東惠民出土一批北朝佛造像, Wenwu 6 (1999): 70–81; and Huimin diqu wenwu guanli zu 惠民地區文物管理組, ‘Shandong Wudi chutu Beiqi zaoxiang’ 山東無棣出土北齊造像, Wenwu 7 (1983): 45–47.

13 Su Bai et al., eds Shengshi chongguang, p.135. Lukas Nickel, Return of the Buddha (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2002), pp.156–57. Edmund Capon and Liu Yang, eds The Lost Buddhas: Chinese Buddhist Sculpture from Qingzhou (Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2008), pp.127–29.

14 Albert E. Dien, Six Dynasties Civilization (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), p.306. Sarah Handler, ‘A Ubiquitous Stool,’ in Austere Luminosity of Chinese Classical Furniture (Berkeley; Los Angeles; London: University of California Press, 2001), pp.82–102.

15 Ōnishi, ‘Hankazō,’ pp.60–64.

16 Using jade ornaments to mark prestigious political and social status had been developed into a ritual system since the Western Zhou period. See Sun Qingwei 孫慶偉, Zhoudai yongyu zhidu yanjiu 周代用玉制度研究 (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 2008).

17 On the ornamentation of Zhucheng Buddhist art, see Matsubara Saburō 松原三郎, ‘Santō chihō tōbu zōzō kō — toku ni shojō shutsudo butsuzō wo chūshin to shite’ 山東地方東部造像考—とくに諸城出土佛像を中心として, in Chūgoku bukkyō chōkokushiron 中国仏教彫刻史論, Vol.1 (Tokyo: Yoshikawa kobunkan, 1995), pp.123–34.

18 Jade ornaments similar to those portrayed on stone Bodhisattvas have been discovered accompanying the remains of human bodies in many sixth-century tombs. Shanxisheng kaogu yanjiusuo 山西省考古研究所 and Taiyuanshi wenwu guanli weiyuanhui 太原市文物管理委員會, ‘Tai-yuanshi Bei Qi Lourui mu fajue jianbao’ 太原市北齊婁叡墓發掘簡報, Wenwu 10 (1983): 13, 15. Wang Kelin 王克林, ‘Bei Qi Kudi huiluo mu’ 北齊庫狄迴洛墓, Kaogu xuebao 3 (1979): 393, pls IV, X. Hebei sheng Cangzhou diqu wenhuaguan 河北省滄州地區文化館, ‘Hebei sheng Wuqiao sizuo Beichao muzang’ 河北省吳橋北朝四座墓葬, Wenwu 9 (1984): 28, 38. Hebei sheng wenwu yanjiusuo 河北省文物研究所 and Zhongguo shehui kexueyuan kaoguyanjiusuo 中國社會科學院考古研究所, ed., Cixian wanzhang beichao bihuamu 磁縣灣漳北朝壁畫墓 (Beijing: Kexue chubanshe, 2003), pp.137–38.

19 For discussions on the transmission of the hourglass-shaped stool with Buddhism, see John Kieschnick 柯嘉豪, ‘Yizi yu fojiao liuchuan de guanxi’ 椅子與佛教流傳的關係, Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology Academia Sinica 69.4 (1998): 739–40. See also John Kieschnick, The Impact of Buddhism on Chinese Material Culture (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003), pp.233–36.

20 Soyoung Lee and Denise Patry Leidy state that ‘the dramatic cascade of the lower garments has prototypes in that of the earlier Northern Wei’. See their paper ‘Sllia: Korea’s Golden Kingdom,’ Orientations 43.5 (2013): 103.

21 Erik Zürcher, ‘Han Buddhism and the Western Region,’ in eds Wilt Lukas Idema and Erik Zürcher, Thought and Law in Qin and Han China (Leiden: Brill, 1990), pp.166–67. A small bronze Buddha statue discovered in Seoul, only 5cm in height, was brought from China to Korea probably as a talisman for personal use. See Won-Yong Kim, ‘An Early Chinese Gilt Bronze Buddha from Seoul,’ Artibus Asiae 23.1 (1960): 67–71.

22 A study on the surnames of the Paekche envoys to China in the fifth and the seventh centuries shows that Chinese immigrants or Chinese descendants very often served as Paekche’s ambassadors to the Chinese court. Best, A History of … Paekche, pp.491–92.

23 The only pensive bodhisattva statue discovered in the territory of Koguryǒ (from modern-day Pyongyang) shows high stylistic similarity to those from Hebei. Korean National Treasure number 118, Cultural Heritage Administration of the Republic of Korea, <http://english.cha.go.kr/chaen/search/selectGeneralSearchDetail.do?sCcebKdcd=11&ccebAsno=01180000&sCcebCtcd=11>. However, this statue is very small (17.5cm high) and easily portable, and therefore its place of production cannot be easily determined. Its stylistic similarity to NT 83 may also suggest a place of origin in the southern part of the peninsula.

24 An envoy from Paekche in 659 spent nine days sailing from the south coast of the Korean peninsula to Hangzhou Bay in Zhejiang. In 847 it took Ennin 圓仁 ten days to sail from the tip of Shandong peninsula to the mouth of the Kum River 錦江 on the south-west coast on the Korean peninsula. In Best, A History of … Paekche, pp.451–52, Jonathan Best states that Ennin departed China from the mouth of the Huai River, but, in fact, Ennin travelled between Shandong and Zhejiang seeking official permission to go to the sea and eventually left from Shandong. See Huang Qinglian 黃清連, ‘Yuanren yu Tangdai xunjian’ 圓仁與唐代巡檢, Bulletin of the Academia Sinica Institute of History and Philology 68.4 (1997): 932–36. For a map of Ennin’s journey, see Valerie Hansen and Kenneth R. Curtis, eds, Voyages in World History (Boston: Cengage Learning, 2016), p.213.

25 For Koguryŏ’s diplomatic contacts with the northern and southern Chinese states and other political entities in the context of overall East Asian international relations in the fifth and sixth centuries, see Taedon Noh (trans. John Huston), Korea’s Ancient Koguryŏ Kingdom: A Socio-Political History (Leiden: Global Oriental, 2014), pp.231–82.

26 Best, A History of … Paekche, p.450.

27 In the contact between Paekche and the Northern Wei in 472, the Northern Wei refused Paekche’s request of taking military actions against its dutiful vassal Koguryŏ. See ibid., p.460.

28 For discussions of Paekche’s cultural evolution in the fifth and sixth centuries, see ibid., pp.499–501. For discussions on the influence of Liang art on the decorative designs of the tile ends and the wide circulation of glazed pottery and celadon imported from the Western Jin (265–316), Eastern Jin (317–420), and Liu Song (420–479), see Kwon, ‘Paekche History,’ pp.75, 78.

29 In Paekche’s struggle for state survival in the sixth century, Buddhism developed along with political reforms. See Jonathan W. Best, ‘Buddhism and Polity in Early Sixth-century Paekche,’ Korean Studies 26.2 (2002): 165–215. King Widŏk 威德王 of Paekche (r. 554–598) used Buddhist activities as a channel for his diplomatic engagement with Japan. See Best, A History of … Paekche, pp.154–56. For Silla’s use of pensive images in foreign relations, see Tamura Encho, ‘The Influence of Silla Buddhism on Japan During the Asuka-Hakuho Period,’ in ed. Shin-yong Chun, Buddhist Culture in Korea, (Seoul: International Cultural Foundation, 1974), pp.201–32. For the influence of Silla’s diplomatic relationship with China on its Buddhist art in the sixth and seventh centuries, see Choe, ‘Shilla and China,’ p.24–67.

30 Kim Pusik 金富軾, Samguk sagi 三國史記, Vol.1 (Seoul: Taeyang sojok, 1972), p.77.

31 Ibid., p.137.

32 Ibid., p.138.

33 Best, A History of … Paekche, p.468.

34 Daoxuan 道宣, Xu gaoseng zhuan, Vol.1 (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 2014), pp.261–62.

35 For a detailed account of Fashang’s teaching, see Takakusu Junjirō 高楠順次郎, ed., Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新修大藏經, 100 vols (Taishō issaikyō kankōkai, 1924–1932), #2065.50.1016b-c.

36 Dong-seok Kwak, ‘Korean Gilt-Bronze Single Mandorla Buddha Triads and the Dissemination of East Asian Sculptural Style,’ in eds Washizuka Hiromitsu, Park Youngbok, and Kang Woo-Bang, Transmitting the Forms of Divinity: Early Buddhist Art from Korea and Japan (New York: Japan Society, 2003), pp.89–90.

37 Denise Patry Leidy with Huh Hyeong Uk, ‘Interconnections: Buddhism, Silla, and the Asian World,’ in eds Soyoung Lee and Denise Patry Leidy, Silla: Korea’s Golden Kingdom (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013), p.146.

38 John Jorgensen, ‘Goguryeo Buddhism: An Imported Religion in a Multi-Ethnic Warrior Kingdom,’ The Review of Korean Studies 15.1 (2012): 78–79.

39 Best, A History of … Paekche, p.180.

40 Tanabe Saburōsuke, ‘From the Stone Buddha of Longxingsi to Buddhist Images of Three Kingdoms Korea and Asuka-Hakuhō Japan,’ in eds Washizuka Hiromitsu, Park Youngbok, and Kang Woo-Bang, Transmitting the Forms of Divinity: Early Buddhist Art from Korea and Japan (New York: Japan Society, 2003), pp.47–50.

41 Songeun Choe, ‘Relationship between Buddhist Sculpture of Shilla and China,’ Korea Journal 40.4 (2000): 49–53.

42 Based on a very limited number of Buddhist sculptures excavated from Sichuan and the similarities between the tile patterns and ceramic between Paekche and the Liang, François Berthier believed that the art of the pensive bodhisattva image in the triad was influenced by the southern dynasties Buddhist art. See François Berthier, ‘The Meditative Bodhisattva Image in China, Korea and Japan,’ in International Symposium on the Conservation and Restoration of Cultural Property: Interregional Influence in East Asian Art History (Tokyo: Tokyo National Research Institute of Cultural Properties, 1982), pp.4–5.

43 For example, the Avalokitêśvara statue commissioned by Zhang Jingzhang 張景章 in 544 has a pensive image on the back. For the images, see Zhongguo shehui kexueyuan kaogu yanjiusuo 中國社會科學院考古研究所, Hebei sheng wenwu yanjiusuo 河北省文物研究所, and Yecheng kaogudui 鄴城考古隊, ‘Hebei Yecheng yizhi Zhaopengcheng Beichao fosi yu Beiyuzhuan fojiao zaoxiang maicangkeng’ 河北鄴城遺址趙彭城北朝佛寺與北吳庄佛教造像埋藏坑, Kaogu 7 (2013): 56–57. The Zhang Jingzhang statue is currently on display in the Yecheng Museum. Another two examples can be seen in Handanshi wenwu yanjiusuo 邯鄲市文物研究所, Handan gudai diaosuo jinghua 邯鄲古代雕塑精華 (Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe, 2007), nos.53, 54.

44 For the discussion on sixth-century Shandong Buddhist cliff carvings, see Robert Harrist, The Landscape of Words: Stone Inscriptions from Early and Medieval China (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2008), pp.93–217. For an archaeological report on Shandong cliff carvings of Buddhist icons, see Zhang Zong 張總, ‘Shandong Licheng Huangshiyai moyai kanku diaocha’ 山東歷城黃石崖摩崖龕窟調查, Wenwu 4 (1996): 37–46.

45 Best, A History of … Paekche, p.180; Best, ‘Transmission and Transformation of Early Buddhist Culture,’ pp.22–23.