Activist Practitioners in the Qigong Boom of the 1980s

![]() Utiraruto Otehode and Benjamin Penny

Utiraruto Otehode and Benjamin Penny

Between the early 1980s and the end of the 1990s, there was a craze for qigong 气功 in China that saw its practise become a mass participation activity. Qigong was no longer the preserve of a small number of people. As with the group exercises performed to public address broadcasts at schools and work units, it had become a part of everyday life. During this period, many previously little-known schools of qigong achieved national popularity in the space of a few years, some gaining millions and even tens of millions of practitioners. One example was Soaring Crane Qigong (hexiangzhuang qigong 鹤翔庄气功), created by Zhao Jinxiang 赵金香 (b. 1934), who first began popularising its practise in 1980.[1] At first, just a few people trained alongside Zhao in public parks, but, within four years, according to their own documents, Soaring Crane Qigong had close to ten million practitioners.[2] This figure is probably exaggerated, but this form of qigong, and others, certainly achieved levels of participation unheard of until the 1980s.

Certain people, who came to be known as activist practitioners (gugan 骨干), played an important role in the popularisation of qigong, acting as intermediaries between the founders of schools and the broad mass of practitioners. A capable activist practitioner was able to popularise a practise in one village or one county and sometimes even across an entire municipality, turning hundreds and thousands of people into regular practitioners. Thus, early in the 1980s, fostering such activist practitioners and harnessing their energies was seen as essential to popularising qigong practise. For example, the then State Sport Commission (Guojia tiyu yundong weiyuanhui 国家体育运动委员会) supported Zhao Jinxiang to run numerous training courses for activist practitioners of Soaring Crane Qigong from across China, enabling its rapid spread.

While academic studies of qigong have tended to emphasise the personal charisma and capabilities of masters and a popular interest in health and spirituality as reasons why certain styles spread rapidly, few have examined the existence and role of activist practitioners. This has meant that we have only seen the two extremities of the qigong boom — the masters and the masses, the apex and base of the pyramid — not the activists who played such a dynamic role in the zone linking the two.

This essay shows how activist practitioners were involved in the popularisation of Soaring Crane Qigong in Luoyang 洛阳 municipality, beginning with an introduction to this style of qigong and its popularisation across the country. Next, we show how the activities of individual activist practitioners were influential in the popularisation process. The third section describes Luoyang’s qigong activist practitioners, and classifies them into three broad categories. Finally, we analyse the ties that bound the activists together. The material we use here was mostly provided by Luoyang activist practitioners themselves, with whom Utiraruto Otehode spent two years between 2005 and 2007 doing fieldwork. During this time, he came to know several dozen people who had been enthusiastic activist practitioners in the 1980s and 1990s from Soaring Crane Qigong, Wisdom Healing Qigong (Zhineng qigong智能气功) and Yan Xin Qigong 严新气功. After the suppression of Falun Gong 法轮功 by the Chinese authorities in 1999, the government sought to ‘rectify’ other qigong schools.[3] As a result, by the time Utiraruto came to do his fieldwork, some people had given up the role of activist practitioner, only continuing their practise personally. Others had moved on to popularise the new government-backed qigong styles aimed primarily at promoting health.[4]

Soaring Crane Qigong

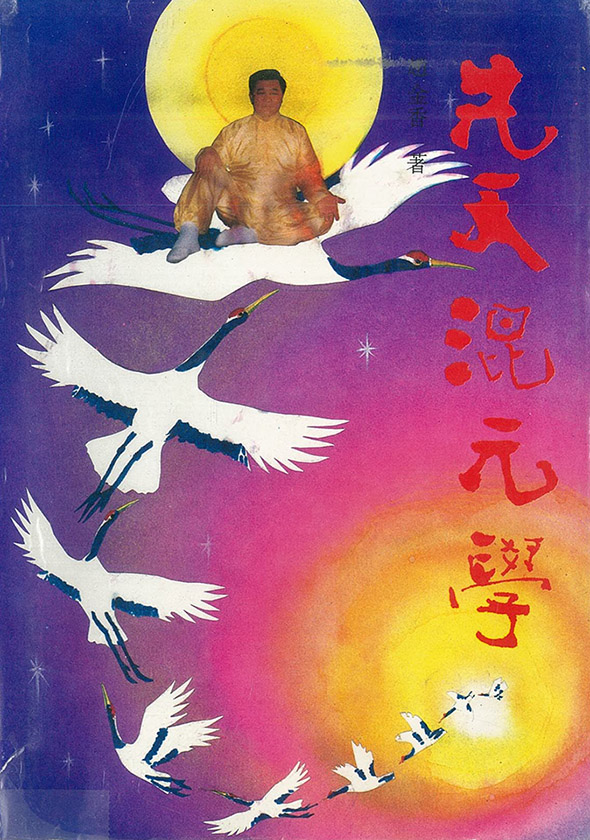

Soaring Crane Qigong was created by Zhao Jinxiang in Beijing in 1980. In Zhao’s own account of the creation of Soaring Crane Qigong, he was born into a peasant family in Shandong in 1937, going to work in Beijing in the 1950s.[5] In the early 1960s while recuperating from illness, he began to practise Liu Guizhen’s 刘贵珍 (1902–83) style of qigong therapy (qigong liaofa 气功疗法) and also began teaching himself traditional Chinese medicine.[6] During a visit home in 1971, Zhao achieved a high level of attainment in Qigong of the Primordial Chaos of the Former Heaven (Xiantian hunyuan qigong (先天混元气功) with the help of a relative. In 1980, he was employed by the Beijing Qigong Research Association (Beijing qigong yanjiuhui 北京气功研究会), where he directed the practise of other devotees. At this time, a number of people suggested he formulate his own set of qigong exercises and in due course, after various revisions, he arrived at the five-part moving qigong exercise that he called Soaring Crane. The crane is traditionally associated with auspiciousness and longevity in China.

Soon after its creation, Soaring Crane Qigong became organised. In 1980, with the formal approval of the Beijing Qigong Research Association, Zhao established a regular teaching venue at the Beijing Workers’ Stadium (Beijing gongren tiyuchang 北京工人体育场). In 1985, he set up the Xiangshan Soaring Crane Research Centre (Xiangshan hexiangzhuang qigong yanjiu zhongxin 香山鹤翔庄气功研究中心) in the western suburbs of Beijing. When the Chinese Research Society into Qigong Science (Zhongguo qigong kexue yanjiuhui 中国气功科学研究会) was established in 1986, the Soaring Crane organisation was included as one of its members. In 1990, Soaring Crane was registered with the Ministry of Civil Affairs’ (Minzheng bu 民政部) Social Organisations (shetuan 社团) division as a subcommittee of the China Association For the Promotion of Culture for the Elderly (Zhonghua laoren wenhua jialiu cuijin hui 中华老人文化交流促进会) — meaning that the Chinese Soaring Crane Qigong Research Committee (Zhongguo hexiangzhuang qigong weiyuanhui 中国鹤翔庄气功委员会) was an officially registered mass-participation social organisation. In 1991, representatives from Soaring Crane organisations in more than ten different countries and regions, including Australia, the USA, the UK, Korea, Japan, Mexico, and Israel, established the International Association for Scientific Research into Soaring Crane Qigong (Guoji hexiangzhuang qigong kexue yanjiuhui 国际鹤翔庄气功科学研究会); Zhao Jinxiang was appointed director-for-life. After the suppression of Falun Gong in 1999, in common with other qigong groups, all Soaring Crane Qigong organisations in mainland China were disbanded.

Zhao Jinxiang and his Soaring Crane Qigong. Zhao Jinxiang 赵金香, Xiantian hunyuanxue 先天混元学 (Beijing: Zhongguo gongren chubanshe, 1994).

Luoyang is in western Henan Province, a four-hour fast train ride from Beijing. Between the early 1980s and late 1990s, dozens of different qigong schools spread throughout the Luoyang area. By 1998, twenty-four different schools were members of the Luoyang Research Society into Qigong Science (Luoyangshi qigong kexue yanjiuhui 洛阳市气功科学研究会) and there were 163 regular venues for teaching qigong, with an estimated 180,000 people practising daily across the municipality.[7] Soaring Crane reached the Luoyang area earlier than other styles of qigong and it had comparatively more practitioners. In 1998, twelve different qigong schools held a combined total of 52 short courses in the Luoyang area, with 9,172 people taking part. Nine of these courses were in Soaring Crane Qigong with 3,804 participants, meaning that it had the best-attended training courses in the city that year. By way of comparison, there was only a single class teaching the nationally famous New Qigong of Guo Lin (Guo Lin xinqigong 郭林新气功), and just eighteen people took part.[8] In 2000, after the suppression of Falun Gong, the Luoyang Research Society into Qigong Science revoked the registrations of the committees representing twenty-four schools of qigong, including Soaring Crane, in line with national policy.[9] Later, some of the former Soaring Crane venues and some of its former practitioners became part of the organisation for the promotion of health-and-fitness oriented qigong sponsored by the State General Administration of Sport (Guojia yiyu zongju 国家体育总局), in which capacity they have continued to the present day.

Soaring Crane Qigong was very active in the Luoyang region throughout the 1980s and 1990s, and can be considered one of the more important centres for the school across the country. Zhao Jinxiang did not visit Luoyang personally to teach before 1989 but his practise had begun to spread there as early as 1981. By 1983, formal classes were being taught in Luoyang and a regular teaching venue had been established in 1985. In Luoyang itself, it was not just ordinary citizens practising Soaring Crane but also senior Communist Party members and government officials. In the early 1980s, a training course for the Standing Committee of the Luoyang Municipal Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (Zhonggong Luoyang shiwei changwei hexiangzhuang qigong xuexiban 中共洛阳市委常委鹤翔庄气功学习班) was held, and consequently many senior figures in the government practised it themselves or supported its practise. By 1995, eleven Soaring Crane teaching venues had been established and there were more than 8,000 regular practitioners.[10] A number of national Soaring Crane events were held in Luoyang: Zhao visited the city four times between 1989 and 1996 to hold national teaching workshops. These workshops each lasted a full week, with some 700 people taking part.[11] Practitioners in the city were especially proud that Luoyang was the location of the Third National Symposium on the Academic Study of Soaring Crane Qigong (Quanguo hexiangzhuang qigong disanjie xueshu jiaoliuhui 全国鹤翔庄气功第三届学术交流会), held in 1990. The Luoyang qigong display team for the Golden Crane Cup (Jinhe jiang 金鹤奖) at this event came first in the competition of 22 regional representative teams.

Activist Practitioners

One practical question faced by many qigong masters and the organisations they led was finding ways to popularise their practise. In the early 1980s, Soaring Crane began to implement a strategy of ‘fostering activist practitioners, and using individuals to achieve wider impact’ (peiyang gugan yidian daimian 培养骨干以点带面) to address this. For example, in late 1982 and early 1983, Zhao held training sessions for activist practitioners in Beijing at the request of the State General Administration for Sport. Trainees came from across China; more than 130 people representing 26 different provincial-level divisions attended.[12] Attendees had been chosen and funded by local official sport administration committees with the intention of taking the practise of Soaring Crane back to their own provinces. Put another way, they were to become the main driver in the promotion of Soaring Crane Qigong, spreading it to their hometowns and regions.

Henan Province’s Sport Administration (Henansheng tiyu weiyuanhui 河南省 体育委员会) sent two people to take part in the Soaring Crane training held in Beijing, one of whom was Zhang Jian 张剑 from Luoyang. Earlier, in 1980, when Soaring Crane had only just begun to become popular, Zhang had trained in the style during a work trip to Beijing. After returning to Luoyang, he taught it in the city’s parks and public squares. Thus, the municipal Sport Administration put his name forward and covered all his costs. Returning to Luoyang, Zhang held courses tailored to senior figures in the municipal Communist Party and government.[13] These classes were held in the main hall of the municipal Party Committee for four hours each weekday evening and all day Sunday. As Zhang recalls, the senior Party and government officials who took part were to play an active role in the promotion of Soaring Crane Qigong in the Luoyang region. The fact that the chair of the municipal Party Committee, the mayor, the chair of the National People’s Congress of Luoyang, and the chair of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference of Luoyang all took part was itself a mark of support for Soaring Crane and excellent publicity. Clearly, the training of trainers in Beijing achieved its desired effect.

Soaring Crane activist practitioners such as Zhang demonstrated the success of the strategy of training individuals to influence the people of their particular locale. At an organisational level, at the headquarters in Beijing and in its local branches, Soaring Crane attached high importance to the fostering of activist practitioners. The chairperson of the Luoyang Soaring Crane Qigong municipal steering committee (Luoyangshi hexiangzhuang qigong weiyuanhui 洛阳市鹤翔庄气功委员会) emphasised, in particular, the power of activist practitioners; over several years, the committee trained hundreds of people who contributed to the teaching and promotion of the style, embodying its principles in their practise. One activist the chairperson mentioned taught Soaring Crane whenever he visited family or friends; in his village alone there were hundreds of practitioners.[14]

Soaring Crane Activist Practitioners in Luoyang

Many activist practitioners of Soaring Crane Qigong emerged in Luoyang during the 1980s and 1990s. They formed the core of the organisation in the city and surrounds — some serving in key posts on Soaring Crane’s municipal committees, and some taking charge of particular teaching venues. Most Soaring Crane activists played a role in its popularisation as teachers and instructors. The three cases discussed below represent three different kinds of activist practitioner. By considering their activities, we can observe what sort of people they were, how they came to be Soaring Crane activists, and what their main contributions to the growth of Soaring Crane practise in Luoyang were.

An Activist Practitioner at the Municipal Level

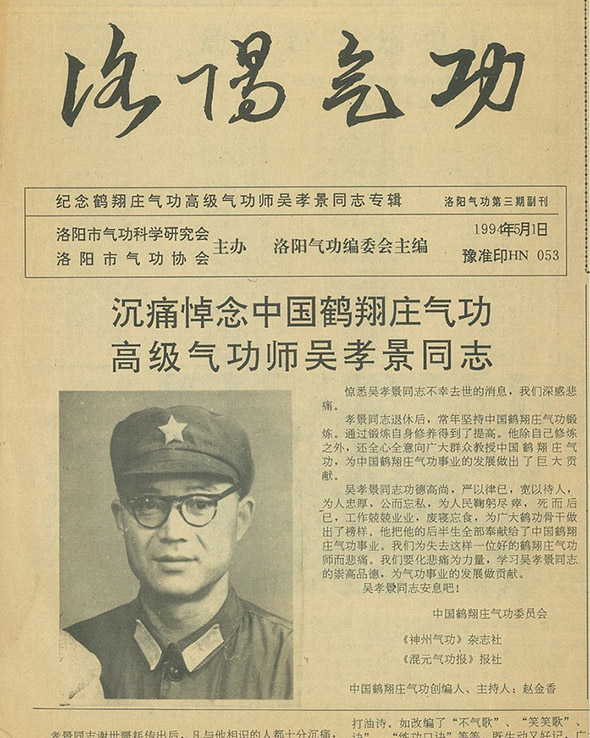

Activist practitioners at the municipal level played an important role in the growth of Soaring Crane practise in the Luoyang region as a whole; most served in key posts on Soaring Crane’s municipal committee. There were only a few activists of this type in the early 1980s, but their numbers steadily increased until there were 40 or so by the early 1990s[15] Wu Xiaojing 吴孝景(1936–93) was a typical municipal-level activist practitioner.

Wu was one of the first to become involved in the popularisation of Soaring Crane in Luoyang and was a key figure in the formation of its municipal steering committee.[16] He believed his practise of Soaring Crane had saved his life.[17] Wu had been in the army, having once served as a political commissar to the People’s Armed Forces Office (Wuzhuang bu 武装部) in Sanmenxia 三门峡. In 1993, he was diagnosed with a tumour on his spleen and underwent surgery in Zhengzhou. After returning to Luoyang, he began learning Soaring Crane in Wangcheng Park 王城公园. Later, while in Beijing for further medical treatment, Wu visited Zhao Jinxiang himself, and received personal coaching. The doctors in Beijing had initially informed Wu that his condition was very serious and that he might not live another six months. Yet, according to his testimony, his health began to steadily improve through practising Soaring Crane. He believed that it had given him a second lease on life and was enthusiastic for more people to study it so that they too could conquer sickness and ill health.[18]

Wu’s contribution to the growth of Soaring Crane practise in the Luoyang region was threefold. Colleagues recall that he held numerous training courses in Luoyang city, in surrounding county towns in the municipality, and in various villages. Secondly, he established the Luoyang Municipality Soaring Crane Qigong Committee as a means of popularising it. Wu placed great emphasis on the role of activist practitioners in this work and held numerous training courses for them. He played a role in the emergence of more than 300 such activist practitioners in the municipality, providing the organisational and personnel resources necessary for its successful popularisation in Luoyang. Thirdly, Wu forged close links between Soaring Crane groups and practitioners in Luoyang and its organisations at the national level. Wu invited Zhao Jinxiang to Luoyang numerous times to hold national-level Soaring Crane events, including training courses for practitioners, academic symposiums, and competitive performances.[19] In March 1993, shortly after the death of Luoyang activist practitioner Wu Xiaojing, Zhao Jinxiang wrote a personal letter to Zhang Jian, another activist in Luoyang. In that letter, Zhao Jinxiang referred to Wu as being ‘reliable’ and ‘the person I was looking for to develop Soaring Crane Qigong’.[20]

An Activist at a Training Venue

The second type of activist worked to promote Soaring Crane Qigong at particular locations in Luoyang municipality. Most were leaders at the regular training venues (Hexiangzhuang qigong fudaozhan 鹤翔庄气功辅导站) in the various parks and public squares of Luoyang city proper that had come into being in the early 1980s. By the 1990s, the number of venues had grown to a dozen or more, with more than twenty activists involved.[21] Since these venues were closest to the everyday life of ordinary people in Luoyang, they played a very important role in the popularisation of Soaring Crane Qigong. Lei Zunting 雷尊廷 (b. 1936) was one such activist practitioner.

Lei was a leader at the Soaring Crane training venue in Wangcheng Park in Luoyang. Formerly a senior aviation engineer, he began practising qigong in 1983 in Wangcheng Park as he only lived ten minutes away. Initially studying Wild Goose Qigong (Dayangong 大雁功) and One Finger Zen Qigong (Yizhi changong 一指禅功), he later switched to the Soaring Crane style. In the early eighties, enthusiasts came together to train informally, but later a more established group of Soaring Crane practitioners formed, and in 1985 a regular training venue was established in Wangcheng Park. Lei took charge of almost all subsequent activities there.[22]

Lei Zunting 雷尊廷 and other qigong practitioners at Wangcheng Park. Lei is wearing a white t-shirt printed with 中国鹤翔庄气功 (‘Chinese Soaring Crane Qigong’) and the efficacious numbers ‘70- 70-70-7’. Photo: Utiraruto Otehode 2005.

The main activities in Wangcheng Park were regular group practise, promotion of the style, and taking part in municipal, provincial, and national Soaring Crane events. Regular group practice took an hour or more every morning at a particular place in the park. There were about 60 regular attendees and about 100 or more irregular attendees. Most lived close by, although a few came from further afield by public transport. The main promotion for Soaring Crane Qigong was through training courses. The Wangcheng Park group put on five such courses in 1990 with 86 people taking part. The regulars would occasionally take part in major competitions or celebrations. For example, Lei and the others from Wangcheng Park were enthusiastic participants in the 1990 Golden Crane Cup competition as well as the 1997 Luoyang display to celebrate the return of Hong Kong to Chinese sovereignty.

An Individual Activist

Individual activists were mostly practitioners of Soaring Crane who had passed Qigong Association tests and had been given permission to become teachers, assistant teachers, or instructors. They assisted leaders at the teaching venues and trained novice students of Soaring Crane. They would also sometimes undertake individual activities aimed at promoting Soaring Crane. In Luoyang, beginning around 1990, there was a fairly well established system for evaluating qigong activists — in 1990, the Luoyang Municipal Soaring Crane Qigong Committee accredited 65 of them,[23] but by 1998, 144 received this qualification.[24] Becoming recognised as an activist practitioner involved passing a number of tests. A certain level of medical knowledge was required as was a high standard of personal morality and behaviour. They were expected to have a thorough grasp of qigong theory, an understanding of its methods, and be skilled instructors.

Han Tianzhi 韩天智 (1924–2008) was a Soaring Crane activist practitioner in Song county 嵩县, part of the wider Luoyang municipality.[25] Han had been director of the county animal husbandry bureau and began practising Soaring Crane after his retirement in 1985. He considered that it improved health and longevity and encouraged moral self-cultivation, claiming that his practise had cured him of illnesses, improved his physical state, and made him a better person. Han said that Soaring Crane required its practitioners first to work to achieve harmony with nature, so they would not harm the environment. Secondly, he said, practitioners should achieve harmony with society, so they were encouraged to make small social contributions as part of their day-to-day lives. Finally, to achieve harmony with their families, they should treat all members fairly and equitably, including treating their daughters-in-law as they did their own daughters.

Han introduced Soaring Crane Qigong to many people and took it to his home village, Checun 车村, which is in a remote mountainous area of Song county some distance from the county town. Before Han returned to teach Soaring Crane in 1993, no-one in the village practised qigong. At first suspicious and unwilling to learn, the villagers believed Han had ulterior motives, but, at its height, more than 40 villagers in Checun were practising Soaring Crane. Han began by working with his relatives, with his younger brother Han Tianlu 韩天禄 taking the lead.[26]

These accounts of practitioners at the municipal, training venue, and individual level show that activist practitioners of Soaring Crane Qigong had a variety of different professional backgrounds and careers: a soldier, an engineer, and a public servant. Other activist practitioners Utiraruto met were peasant farmers, shopkeepers, and housewives. They also had different reasons for becoming Soaring Crane activists. Some thought qigong practise had saved their lives, and wanted to spread it as a way of repaying the debt. Some enjoyed it as a hobby, taking pleasure in spending an hour each day practising with a group. Some were motivated more by ethical or possibly even religious feelings.

The Ties That Bound Activists Together

While relations between the creators of qigong schools and activist practitioners took place in and were mediated by state-registered social organisations such as qigong research associations and steering committees of various schools, activist practitioners and their leaders were also linked in ways outside the state system. Officially, activist practitioners served in mundane and visible roles as committee chairs, committee members, or instructors. Outside that system, the links between activists were cultural and spiritual, being built on foundations from Chinese tradition, religion, and folk belief.

The spiritual ties in Soaring Crane were embodied in the relationship between its creator and the local activists. In his letter to Zhang Jian referred to above, as well as praising Zhang Jian and the other core activists in Luoyang for their handling of Wu Xiaojing’s funeral arrangements, Zhao Jinxiang also gave an account of the place now held by Wu in the spirit world:

… Wu Xiaojing has appeared before me many times. He wished to say farewell and also to tell me that he would believe in Soaring Crane and in his master Zhao Jinxiang for all eternity. He has already been granted his place, immutable and undying in the cosmos. He is a mighty general in the cosmic realm, the Red Lord [Hongbanzi 红斑子]. He has been given charge of the weather, whether it will be cloudy or fine, whether the wind will blow or the rain fall. He told me that, if need be, he can manifest his spirit powers to aid Soaring Crane.[27]

Clearly, the relationship between Zhao and activists in Luoyang was spiritual in nature: the relationship between Zhao and Wu had not come to an end merely because the Wu Xiaojing who lived in our world had died. Indeed, they appear to have frequent spiritual interaction and their spiritual relationship is, if anything, closer than ever.

Soaring Crane activists also believed that Zhao Jinxiang had spiritual powers. To cite one example, the wife of one young Luoyang activist, Mr Hu, was several months pregnant. During a hospital check-up the doctor told her she was going to have a girl, but Mr Hu wanted a son. Not long afterwards, Zhao Jinxiang visited Luoyang, and Hu asked Zhao if there was any possibility that he might have a boy instead. Zhao simply said, ‘You can have a son’. While subsequent check-ups consistently showed a girl, when the baby was born it was indeed a boy. Mr Hu said this was definitely the result of Zhao using his spiritual powers. Another activist, a Mr Liu, also had personal experience of Zhao’s powers. Liu had taken part in a training course for Soaring Crane activists in the 1990s and Zhao had instructed that photographs were not to be taken without permission. Nonetheless, Liu wanted to take a photograph and when the master’s attention was elsewhere, did so. When Liu had his film developed, the one of Zhao Jinxiang only showed a miasma of multicoloured light — all the other photographs on the roll developed as expected. Liu considered himself lucky to have been able to photograph Zhao’s spirit aura.

These spiritual links between Soaring Crane practitioners and their master played a special role in its popularisation, as it enabled a direct relationship between Soaring Crane’s creator and its grassroots activists. Relationships such as these were obviously unlike those established according to the state regulations governing social organisations — they were informal and invisible and not subject to oversight by administrative organs of the state. In addition, we should be aware that behind the dry, bureaucratic, and officially sanctioned instructional books and magazine articles emanating from qigong groups through the 1980s and 1990s often dwelt strong and privately held beliefs in the minds of practitioners in the spiritual powers and cosmic roles of their practices and masters.

Conclusion

While the personal capabilities or charisma of any qigong master in the 1980s and 1990s were important in the rapid spread of qigong in mainland China, we should also direct our attention to the great number of activist practitioners across the country who worked hard to popularise and promote the various styles. We should also note that at the beginning of the qigong boom in the early 1980s, government agencies at both central and local levels gave their support to, and even became directly involved in, activities aimed at fostering activist practitioners. We have seen how the hundred or so trainees at the first national course for qigong activists had been recommended by their local governments, who also covered the costs of attending the course. At a minimum, this indicates that in the early 1980s relations between the state and qigong masters were cordial and that they worked together to train activists and spread qigong among ordinary people nationwide.

The degree to which qigong actually spread and took root in a given place was, in large part, due to its local qigong activists. In addition, some styles of qigong were popular in some localities but not in others, and in some places more than one style was practiced while in others only one could be found. This depended to a large extent on whether or not a group of activist practitioners were there, and the degree to which a group was effective or not in organisation and action. In the case described here, Soaring Crane succeeded in becoming very popular in the Luoyang region because of the strong organisation and the capacity for action by a large group of activist practitioners.

The existence of relationships between the qigong masters and local activist practitioners outside the state system, such as the spiritual bonds described above, enabled qigong forms to survive and grow. These relationships were generally well hidden — unlike the links based on social organisations, these spiritual ties did not appear in any formal documents. They were grounded on private correspondence or word of mouth, but nonetheless coexisted harmoniously with the formal relationships, and sometimes even served to strengthen the working of, the official organisations — such as the numerous occasions on which the Luoyang Soaring Crane Municipal Steering Committee assisted Zhao Jinxiang in holding training courses and research symposiums. Yet the existence of such relationships in itself constituted a potential threat to the state’s means of control of social organisations because qigong masters could directly influence the activities of local activists through invisible and informal networks that escaped oversight and control by the state.

In the end, after the suppression of Falun Gong, the government disbanded all qigong organisations and began the nationwide promotion of a newly formulated health-and-fitness style of qigong (jianshen qigong 健身气功) instead. Not only was Luoyang chosen as a test location for the promotion of this new ‘healthy’ qigong, the campaign there met with great success. Ironically, perhaps, many formerly devoted practitioners of Soaring Crane Qigong became active in the new qigong association and became instructors at its training venues in the city’s parks.

Utiraruto Otehode

School of Culture, History and Language

College of Asia and the Pacific

The Australian National University

wuqi.riletu@anu.edu.au

Benjamin Penny

Australian Centre on China in the World

College of Asia and the Pacific

The Australian National University

benjamin.penny@anu.edu.au

1 For a medical-anthropological approach to Soaring Crane Qigong, see Thomas Ots, ‘The Silenced Body: The Expressive Leib: On the Dialectic of Mind and Life in Chinese Cathartic Healing,’ in Thomas J. Csordas, Embodiment and Experience: The Existential Ground of Culture and Self (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), pp.116–36.

2 ‘Hexiangzhuang qigong quanguo shoujie xueshu jiaoliuhui ziliao huibian’ 鹤翔庄气功全国首届学术交流会资料汇编, Tiyu Bao 体育报 13/8/83, p.1, gives the number of Soaring Crane practitioners nationally in August 1983 as 4,500,000.

3 See, Benjamin Penny, The Religion of Falun Gong (University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 2012).

4 Utiraruto Otehode, ‘The Creation and Reemergence of Qigong in China,’ in eds Yoshiko Ashiwa and David L. Wank, Making Religion and Making the State: The Politics of Religion in Modern China (California: Stanford University Press, 2009).

5 Zhao Jinxiang 赵金香, Xiantian hunyuanxue (先天混元学), (Beijing: Zhongguo gongren chubanshe, 1994), pp.134–40.

6 Utiraruto Otehode and Benjamin Penny, ‘Qigong Therapy in 1950s China,’ East Asian History 40 (2016): 69–83.

7 These figures are taken from Luoyang shi qigong kexue yanjiuhui jiuba nian gongzuo zongjie ji jiujiu nian gongzuo jihua (洛阳市气功科学研究会九八年工作总结及九九年工作计划 Luoyang Research Society into Qigong Science Work Report for 1998 and Plan for 1999).

9 The revocation followed instructions given in the joint General Office of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party and General Office of the State Council (Zhonggong zhongyang bangongting, Guowuyuan bangongting 中共中央办公厅,国务院办公厅), 6 (2000), ‘Zhuxiao huo chexiao an qigong gongfa, leibie chengli de qigong shetuan ji fenzhi jigou’ 注销或撤消按气功功法, 类别成立的气功社团及分支机构.

10 Hunyuan qigong bao 混元气功报 October 1995, p.4.

11 According to notes supplied to Utiraruto Otehode by a Mr Lei 雷, head of the teaching centre in Wangcheng Park.

12 Zhao Jinxiang, Xiantian hunyuanxue, p.144.

13 Recalling events in 2006, Zhang Jian said the full title given to this training course was Soaring Crane Qigong Training Course of the Standing Committee of the Luoyang Municipal Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (Zhonggong Luoyang shiwei changwei hegong xuexiban 中共洛阳市委常委鹤功学习班).

14 Wang Xingwen 王星汶, quoted in Hunyuan qigong bao, October 1995, p.4

15 In a 2006 interview that Utiraruto Otehode conducted with Zhang Jian 张剑 and Lei Zunting 雷尊廷, he was told that in the early 1980s activists in the popularisation of Soaring Crane included his two interlocutors, along with Tian Songlin 田松林 and Wu Xiaojing 吴孝景. The figure for 1993 is derived from a list of members of Luoyang Soaring Crane Municipal Steering Committee.

16 Duan Cunying 段存英, widow of Wu Xiaojing, assisted Utiraruto Otehode during fieldwork conducted in Luoyang between 2005 and 2007.

17 Wu Xiaojing, ‘Wo — you yige jeuzheng feng shengzhe’ 我―又一个绝症逢生者 (‘Here am I, another person saved despite terminal illness’), private paper dated 1985.

18 Wang Xingwen, ‘Yige hao bu liji zhuanmen li ren de ren’ 一个毫不利己专门利人的, supplement to Luoyang qigong 洛阳气功, May 1994.

19 ‘Jinian hexiangzhuang qigong gaoji qigongshi Wu Xiaojing tongzhi zhuanji 纪念鹤翔庄气功高级气功师吴孝景同志专辑, Luoyang qigong 洛阳气功 May 1994.

20 Zhang Jian provided this letter to Utiraruto Otehode in 2006.

21 Materials held by the Luoyang Municipality Soaring Crane Qigong Committee noted training centres in nine locations in 1993, with between one and three leading activists at each for a total of sixteen such persons. By 1996, there were twelve centres, each with between one and four leading activists for a total of 26 such persons.

22 During fieldwork undertaken in Luoyang between 2005 and 2007, Utiraruto Otehode was a long-term participant in activities run by Lei Zunting at the Wangcheng Park Soaring Crane training centre, and acknowledges the care and assistance Lei provided.

23 According to the committee’s 1990 work report, nine of these 65 were evaluated as Grade Two qigong teachers, 25 as assistant teachers, and 31 as coaches.

24 The committee’s 1998 work report stated that 23 of these 144 were evaluated as qigong teachers, 46 as assistant teachers, and 75 as coaches.

25 Utiraruto Otehode visited Han Tianzhi at home several times in Song county in 2006, conducting long discussions with him. The account here is drawn from notes taken during those conversations.

26 This part of the account draws on a survey Utiraruto Otehode conducted in Checun 车村 in September 2006. During the same visit, he interviewed Han Tianlu and other Soaring Crane practitioners.