Editor’s Preface

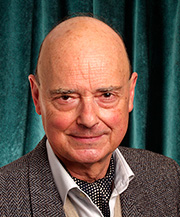

![]() Benjamin Penny

Benjamin Penny

The number forty has long been held to be unlucky in the cultures of East Asia. Perhaps this accounts for the various unfortunate occurrences that have beset and delayed the publication of this issue of East Asian History. I am, however, very pleased now to be able to launch a number of the journal that reflects the quality, originality, and breadth of scholarship in research on the histories of Japan, Korea, and China. In this issue, in addition to research articles than span a breadth of time from the seventh century to the 1950s, Nathan Woolley presents an online exhibition based on Celestial Empire: Life in China 1644–1911. Celestial Empire, curated by Dr Woolley, was a major exhibition staged at the National Library of Australia in collaboration with the National Library of China from January to May 2016. The online exhibition presents 29 of the objects that made up its non-virtual equivalent, along with an introductory essay.

In the Preface to the last issue, it was my sad duty to note the passing of Professor Pierre Ryckmans. In recent weeks, another of the outstanding scholars of East Asia, and periodic contributor to this journal, has left us. Igor de Rachewiltz was perhaps the greatest historian of Mongolia and Mongolian period China of his generation. Graduating with his doctorate on Yelü Chucai 耶律楚材 from The Australian National University in 1961, Igor is perhaps best known for his monumental and extraordinary The Secret History of the Mongols: A Mongolian Epic Chronicle of the Thirteenth Century, Translated with a Historical and Philological Commentary, which was published by Brill in three volumes from 2004 to 2013.

A remarkably productive scholar, Igor’s work received worldwide recognition and awards. He was made a Fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities in 1972 and an Honourable Member of the International Association for Mongol Studies, Ulan Bator in 1992. Six years later, in 1998, he received the Diploma of Honour of the International Centre for Chinggis Khan Studies, Ulan Bator; a Knight of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic in the same year; followed by an Honorary Doctorate in Letters and Philosophy from the Faculty of Letters and Philosophy, University of Rome ‘La Sapienza’ in 2001; a Centenary Medal for Service to Australian Society and the Humanities in Asian Studies in 2003; and the Gold Medal of the Permanent International Altaistic Conference in 2004. He was also signally honoured by the awards of the Polar Star Medal of the Mongolian Republic and the Denis Sinor Medal of the Royal Asiatic Society, London in 2007. These extraordinary achievements may give the impression of a serious and unapproachable scholar. Igor was anything but this: he was a delightful and witty man, stylish to the last, friendly, supportive and humble about his attainments.

For the past few years, Igor was based at the Australian Centre on China in the World at The Australian National University. Over his last months, typically reluctant though he was initially, Igor was kind enough to work with us to make a selection of his articles and book chapters that were, to his mind, the most valuable and the hardest to find. Many of his publications in journals, including those in East Asian History, are now of course, available online. However, Igor also published work in volumes of essays, festschrifts, and in journals that are only available in print and are often difficult to locate. Over the next few issues we will be republishing many of these articles and essays, including selections of both his more historical and his more philological work. Sad as we are that a great scholar, teacher, and friend is no longer with us, we find some consolation in knowing that a project Igor worked on with us will act as a small memorial to a great man.