Editors' Preface

![]() Benjamin Penny and Remco Breuker

Benjamin Penny and Remco Breuker

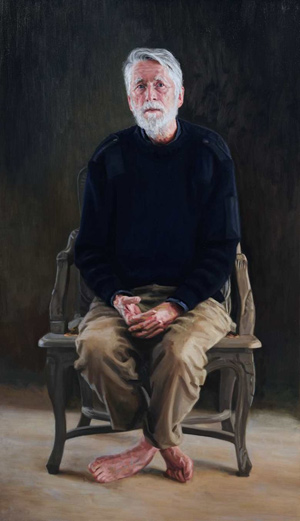

On August 11 this year, Pierre Ryckmans doyen of Sinologists, mentor of many in Australia and around the world, novelist, essayist, scholar and friend, died at the age of 78. His passing has affected many in our field deeply. In our next issue of East Asian History, we will publish an appreciation of his life and work by Geremie R. Barmé, one of his students, as well as reprinting a small selection of his work.

In this issue, however, we feature the work of Frits Vos. Vos (1918–2000) was Professor of Japanese and Korean Studies at Leiden University from 1958 to 1983. Famous as a scholar of great erudition and breadth of scholarship, he also established Korean Studies at Leiden University as early as 1947 and was widely known for his wit, his love of jazz and his translations of Japanese and Korean literature into the Dutch language.

Entering university in 1937, he majored in Chinese and Japanese Studies. During World War II, when the university had been closed down, he learned Korean from a German missionary who found himself in Leiden. Later he would also study classical and contemporary Mongolian and Ainu, but his academic activities were characterised by a dual love for Japan and Korea. Although he was initially going to be appointed as Professor of Japanese Language and Culture, he insisted that his terrain as a full professor and chair holder would be extended to include Korea.

Vos obtained his doctorate with A Study of the Ise Monogatari in 1957. He published around 130 books, articles and translations, including Die Religionen Koreas (1977), and together with legendary Sinologist Erik Zürcher a monograph on Zen/Chan/Sŏn Buddhism in Dutch, Spel zonder snaren: enige beschouwingen over Zen (1964). Throughout his academic career, Vos tried to balance his interests in Japan and Korea, resulting in studies such as ‘Kim Yusin, persönlichkeit und mythos: ein beitrag zur kenntnis der altkoreanischen Geschichte,’ Oriens extremus 1 (1954) & 2 (1955) on the general who unified the Korean peninsula in 668; ‘Forgotten Foibles: Love and the Dutch at Dejima (1641-1854),’ in Asien tradition und fortschritt: festschrift für Horst Hammitzsch zu seinem 60. Geburtstag (1971), pp. 614–33, on the sexual proclivities of Dutch merchants in Deshima, and critically acclaimed translations into Dutch of classic Korean poetry — Liefde rond, liefde vierkant, zeven eeuwen Koreaanse liefdespoëzie, from 1981 — and of the eccentric Japanese Zen Priest Ryōkan — Gedichten van de excentrieke Zen-priester Ryōkan (1759–1831), in 1996.

As a young man, Vos participated in the Korean War, where he acted as interpreter and translator with the rank of captain. His experiences there would keep informing his life outside the walls of academia. World War II had immensely complicated Dutch–Japanese relations and fierce national debates raged throughout the Netherlands, largely coinciding with Vos’s tenure as professor. He did not shirk his responsibility and often inserted the voice of academic reason into these heated debates. His participation in the first Dutch post-war trading mission in 1965 made clear his resolution to play an active part in the restoration of Dutch–Japanese relations. In 1975, he helped establish the Japan–Netherlands Institute in Tokyo, and when the French Embassy in The Hague was occupied by Japanese left-wing radicals, he was asked by the then prime minister to act as an advisor. Vos and his wife, Miyako, would come to maintain direct contact with the occupiers of the embassy.

Institutionally, Vos also left his mark. He was one of the founders of the European Association for Japanese Studies (1973); he served as the first president of the Association for Korean Studies in Europe (1977); and, perhaps most importantly, he made possible the establishment of Korean Studies as an independent major at Leiden University. Vos was bestowed with many different awards, prizes and even imperial honours from Korea and Japan, but his lasting legacy is the breadth and depth of his scholarship and the sophisticated yet irreverent wit that still make his studies worth reading.

Most of Vos’s scholarly output was not in English, but we are fortunate that three fascinating essays were, and these we reprint in this issue of East Asian History. We hope that by doing so, readers will be encouraged to seek out his other works and discover, or rediscover, this major scholar.