Mapping The Social Lives Of Objects:

![]() James Beattie & Lauren Murray

James Beattie & Lauren Murray

I see on the mantelshelf the pale wood

Chinese tea-caddy my friend gave me; …

… Only smoothness is broken by the incised beautiful

characters, red and black I cannot read,

and on two sides the mountain and the water

and the pine-tree, on a third the scholar

fiercely bearded, fiercely ecstatic, consumed

with a holy flame inveterate, wringing

joy from his classic. I stroke the cool bamboo,

I am lifted away, to the steep slope

of the mountain, under the pine, I see

myself curious, meditative, composed,

mirrored in water, standing on pine-needles;

unseen beside the scholar, I too read …

J.C. Beaglehole [1]

Chinese art is quite a recent invention,

not much more than a hundred years old.

Craig Clunas [2]

How is one to understand and respond to objects taken out of their original cultural and historical contexts? The quotations above hint at the complex epistemological problems which lie at the heart of cultural engagement across societies.

For J.C. Beaglehole (1901–71), a part-time poet better known today as the biographer of James Cook, cultural engagement demanded imaginative and creative interaction with the “Chinese” object itself, a process literally transporting the viewer into its “art world”. Writing over sixty years after Beaglehole, for art historian Craig Clunas, the artistic re-categorisation required to engage with an object from another culture, as Beaglehole did, can reveal much more about the individual from the society interpreting the object than it can about the creative endeavours which went into the object’s manufacture. Indeed, at first reading, Clunas’s statement appears curious. After all, does China not possess a rich material culture of over 3000 years? Its meaning, however, becomes clear when one considers Clunas’s assertion elsewhere that “Art” is less “a category in the sense of a pre-existent container” so much as “a way of categorising, a manner of making knowledge”.[3]

This article develops Clunas’s standpoint, specifically through an examination of the reception and circulation of Chinese objects in New Zealand. Based on the case study of a major exhibition of “Chinese Art” held in New Zealand in 1937, we argue that the study of objects and their inscribed meanings as they travel between cultures and through time can reveal significant patterns of cultural exchange and influence. An understanding of how objects “constitute and instantiate social relations”[4] can illuminate their role in shaping perceptions of the different cultures within host societies. As Arjun Appadurai has argued, a “biographical” approach to the study of objects and their physical circulation can expose processes of reception and re-contextualisation which determine both the meaning attributed to an object within a host culture and constructions of the society which produced it.[5] Where linguistic, geographical or cultural differences hinder other forms of cross-cultural communication, the varied meanings of objects—their polysemantic capacity—thus allows forms of cultural translation to occur which are otherwise impossible in other media. This article first examines objects and the historiographical issues they raise through human interaction with them. Next, it presents a short overview of Western attitudes towards Chinese objects, before analysing in detail the reception and polysemantic capacity of Chinese objects brought to New Zealand through the 1937 Exhibition.

Objective Knowledge of China

Susan M. Pearce sees “object” as analogous to “thing”, “specimen” or “artefact”. “[A]ll of these terms”, she notes, “share common ground … all refer to selected lumps of the physical world to which cultural value has been ascribed”.[6] This not only refers to individual objects capable of being transported by humans, “but also the larger physical world of landscape with all the social structure that it carries”.[7] Pearce’s expansive definition raises several questions. Not least of those is the process of how societies “ascribe cultural value” to objects, and how they define and measure them. An object’s valuation corresponds closely to its meaning to individuals who engage with it, both visually and in a more tactile sense. Meaning, then, is not static; not an immanent characteristic of an object. An object can simultaneously carry a number of potentially contradictory meanings, with “no ultimate or unitary meaning that can be held to exhaust it”.[8] It is this perspective that we use as a starting point for our analysis of Chinese art in 1930s New Zealand.

But before examining our case study, it is important to consider both how value is assigned to an object and, more specifically, how Chinese objects reached New Zealand. With movement and the passing of time, an object’s status grows more complicated, especially when it travels across social or cultural boundaries. In “Commodities and the Politics of Value”,[9] Appadurai follows Igor Kopytoff’s notion that objects possess life histories and move through a number of interpretive “phases”.[10] An important aspect of the lives of objects is “their capacity to act as goods to be exchanged and hence to carry values”.[11] For Appadurai, exchanges can involve parties which hold different “regimes of value”[12] and can result in the re-contextualisation of the object as it completes the process of exchange and enters a new cultural and social milieu. Chinese objects which have travelled to the West often fall into this special category. Pearce, for instance, remarks that “the acquisition and interpretation of material from” beyond the West “has its own world of politics”.[13] It is a world of politics predicated upon the long, complex and—not least—tumultuous history of cultural encounter between China and Western societies in which geographical distance across Eurasia has often proved as vast as the cultural differences between West and East.

For most people, encounters took place as exchanges of material culture resultant of wider trade networks. Over time, perceptions of Chinese culture in the West drew from interpretations of the diaspora of Chinese objects, a dynamic process of re-contextualisation in which objects at once came to “stand for the culture whence they came”—as exemplars of the “race” which produced them—and stimulate new aesthetic responses to a category deemed to be “Chinese art”.[14] As a colony of Britain, New Zealand’s white culture drew much from contemporary debates in that country, so it is therefore instructive to examine British attitudes towards Chinese objects and how they influenced collecting practices and opinions in New Zealand.

The Social Lives of Chinese Objects in Europe

The history of European engagement with China and Chinese objects belies the notion of a relatively recent dating of Western fascination with Chinese culture. Trade between the two regions began as early as the seventh and sixth centuries BCE, with the Scythians sourcing gold from the Tian Shan 天山 mountains. Continuing intermittently, that trade gained momentum through the high value placed by the Roman Empire on silk, spices and other Chinese products. Trade links provided the impetus for continued cultural contact over the ensuing centuries. The advanced material and technical cultures of Chinese societies during this time all but ensured the one-sided flow of manufactured goods across the Eurasian landmass from China to Europe. Over time, thanks to the strengthening of European maritime contacts in the vigorous local Indian Oceanic trade networks, what had been a percolation of Chinese textiles, porcelain and furniture, reached a stream in the seventeenth century and something of a flood by the eighteenth century as a craze for things Chinese swept up polite European and North American society.[15]

Elements of Chinese design, architecture and aesthetic styles began to be imitated by many European manufacturers as they produced cheap import substitutes in an attempt to cash in on the mania for Chinese objects.[16] Indeed, for world historian Robert Finlay, the development of a vigorous exchange of styles and designs by the eighteenth century constituted the world’s first global style, “a collective visual language” in ceramic art as Finlay puts it.[17] That visual style, chinoiserie, came to denote “the European manifestation of … various styles with which are mixed rococo, baroque, gothick or any other European style it was felt was suitable.”[18] Objects displaying chinoiserie design elements represented, as Oliver Impey writes, “the European idea of what oriental things were like, or ought to be like,” an interpretation based on a “conception of the Orient gathered from imported objects and travellers’ tales”.[19] Impey classifies that fashion into three rough phases, dating from the sixteenth century. From its origins as a style of decorating objects such as furniture and ceramics, to the architectural layout of gardens and even buildings which were otherwise essentially European in composition, chinoiserie decoration “took over the European shape and altered it more drastically”.[20] Melded with the rococo style which was gaining popularity in the 1730s–1740s, it glamorised, as David Porter notes, “the unknown and unknowable for its own sake”.[21]

Scholars of literature such as Porter view chinoiserie as an innately Western response to the problem of conceptualizing other races and cultures. For him, “to luxuriate in a flow of unmeaning Eastern signs, to bask in the glow of one’s own projected fantasies” explains chinoiserie’s chief appeal, an appeal which counteracted ideas of China promulgated by earlier cultural authorities like Matteo Ricci (1552–1610), as well as by other Jesuits and later Enlightenment philosophes, who envisaged China as a rational civilised alternative to a Europe stultified by superstition and dulled by decadence. Indeed, as Porter writes, “China became in chinoiserie a flimsy fantasy of doll-like lovers, children, monkeys, and fishermen lolling about in gardens embraced by eternal spring” lacking in substance.[22] Yet, to parse the two views is perhaps not wholly accurate. The same enquiring impulse which upheld China as a viable intellectual and social alternative to Europe originated in many ways in the same wellspring of ideas about chinoiserie that espoused Chinese objects’ whimsical and feminine aspects.[23] (Taste for chinoiserie, indeed, became highly gendered, a reflection of the broader depiction of Eastern societies as highly feminised.[24]) By the late-eighteenth century, interpretations of China were also changing. Interaction and increasing knowledge, coupled with European trade rivalry, forced a re-evaluation of China and its material products.

By the nineteenth century as Western and, later Japanese, forces first nibbled away, then greedily gouged out parts of China’s coastal territory, the European Enlightenment image of China as an exemplar of a rational, ordered and highly sophisticated civilisation gave way to one of a spent, worn-out culture, ruled by despotic leaders, desperately mired in the past. It was an image of a people as much as anything symbolised by the oppressed Chinese coolie, a living anachronism burdened in a rapidly moving present by the accumulated problems of China’s stultifying backwardness.[25] Some-what paradoxically, the more violent encounters between European powers and China, manifested in the Opium Wars (1839–42; 1856–60) and the ransacking of the old Summer Palace (Yuanmingyuan 圓明園) in Peking in 1860 forcefully exposed Europeans to objects far different from those encountered through chinoiserie and produced by Chinese factories for the European export market. Violence stimulated Western interest in art objects also produced for, and appreciated by, Chinese elite, in other words of objects of a much higher quality than those previously encountered. Notwithstanding the perceived degraded culture which currently was in evidence, an ingenious intellectual sleight of hand enabled the valuing of certain Chinese objects in European circles. As Clunas shows, Europeans could value objects produced in earlier periods of China’s history perceived as representative of higher “civilisational” achievement. That meant everything up to the Qianlong 乾隆 emperor (r. 1736–95) could be collected, but, generally speaking, nothing beyond as, to Europeans, the later Qing 清 dynasty (1644–1911) and its cultural productions symbolised the degraded and impure modern nation into which China had fallen.

In this sense, the sacking of the Summer Palace in 1860 by Anglo-French forces violently brought Europeans face-to-face for the first time with exquisite and delicate objects of élite Chinese and imperial provenance.[26] While piled up in the still-smouldering ruins of the emperor’s pleasure grounds, the newly looted objects took the first step of their newly re-inscribed cultural life. Participating in a “tournament of value,” objects were auctioned off among the soldiers and officers who had helped to destroy the palace complex.[27] Each soldier received a cut of the auctioned booty, commensurate to his military rank. As James L. Hevia argues, “these processes of collection, auction and redistribution of proceeds organised Chinese imperial objects within a moral order of law and private property, implicating them in a schema of values and concerns that neutralized the dangers they posed to order”.[28] In Europe, ex-imperial objects were imbued with the significance of the narrative of their acquisition,

inscribed for a time with signs indicating the triumph of order over disorder, of officers over men and of the Anglo-French expeditionary force over the “arrogant” and “treacherous” Qing government whose torture of prisoners had provoked this symbolic response. In the last case, the objects came to bear another meaning as well; imperial humiliation.[29]

This event served as one paradigm of the nineteenth-century wave of diasporic Chinese objects, which played a major role in shaping new understandings of Chinese material culture within European societies.

The next phase of the “social lives” of some of the objects from the Summer Palace occurred with their removal to England and consequent re-contextualisation as objects within a discourse of colonial power. Clunas, Impey, Hevia and Nick Pearce all view the influx of elite and imperial Chinese objects as a catalyst for a tectonic shift in classification and valuation of Chinese material culture in the latter decades of the nineteenth century.[30] For Clunas, “the creation of “Chinese art” in the late-nineteenth century allowed statements to be made about, and values to be ascribed to, a range of types of objects.” Statements about “art” were, he notes, “all to a greater or lesser extent … about ‘China’ itself”.[31] Chinese objects “owned” by those in the West were re-imagined as symbols of a faded Chinese imperial glory and set in motion within a network of cultural projections and interpretations which reproduced the dynamics of contemporary political discourses and created powerful tropes of a once glorious Chinese civilisation subjugated and patronized by a technologically and morally superior West. The seductive appeal of such discourses was evident in the systems of representation and display which were used to ascribe value to imperial objects within the public realm.

Most imperial objects were held by private collectors, but from 1861–65 objects from the Summer Palace were publicly displayed on at least three occasions in Paris and London.[32] At those times, at least, the narratives of humiliation and defeat surrounding China resulted in the aesthetic denigration of the objects on display. In particular, the objects elicited unfavourable comparisons “with the recently revealed artistic achievements of its neighbour,” Japan.[33] However, with the growth in new forms of production and dissemination of knowledge structured by “global natural historical or cultural taxonomies which were inseparably bound up with the Victorian passion for classification,” interpretations of Chinese material culture again began to change.[34]

This re-contextualisation was facilitated, as much in the West as, in certain contexts, in late imperial and republican China, by the rise of museums and “international exhibitions” and their usefulness in both controlling public debate and shaping a “national consciousness”.[35] In the case of Chinese objects, in the West the growth of archaeological and anthropological discourse led to the valuation of Chinese objects and material culture as repositories of cultural and racial information which could be uncovered through application of scientific methodologies, and ideally arranged taxonomically in a museum exhibition space. The rise of the exhibition and of the institution of the museum during this period exemplified these new forms of cultural knowledge. Although Chinese “civilisation” was initially situated within a continuum of racial evolution at the head of which—perhaps unsurprisingly—were situated objects produced in Europe, long-standing European admiration for Chinese material culture (though not necessarily Chinese people), and the consequent high value placed on many Chinese objects, meant that they attracted competing interpretations and values: indeed, the ownership of beautifully-wrought objects once held in imperial or élite collections came, in certain hands, to confer prestige on the new object’s owner.

Great debates raged in nineteenth and early-twentieth-century North America and Europe as to whether Chinese items constituted art or ethnography.[36] The rise of ethnography lent classificatory weight to viewing objects as comprising inherently ethnographical information about the culture which produced it. Even when the objects became viewed as art towards the latter nineteenth century, the taxonomic impulse, according to Clunas, remained prevalent in British institutions (and, as we show, also in New Zealand’s 1937 Exhibition). He cites the example of the British Museum, which received its first Chinese objects from a bequest by Sir Hans Sloane (1660–1753) in the year of his death. Initial classification placed the objects under the rubric “Ethnography”, although by the mid-nineteenth century this had shifted to reflect changing European notions of art. European hierarchies of art, enshrining painting (especially in oil of the human form) as the highest form of aesthetic achievement, accorded Chinese painting a place as “art”, albeit under the slightly lesser category of “prints”. By 1913, the Museum established a sub-department of Oriental Prints and Drawings, thus demonstrating the taxonomic re-classification of images produced in China. Meanwhile, the South Kensington Museum (from 1889, the Victoria and Albert Museum), established in 1851 to display ornamental art as models to improve British manufacturing, struggled by the new century to classify its collection of Chinese ceramics, a position resolved in the inter-war years as its Department of Ceramics folded together the categories of porcelain and art.[37]

These and other museums catered to the leisured demands of increasing numbers of the British middle classes. Many aspired to possess the trappings of their social betters. From the late nineteenth century, British department stores, historian of design Sarah Cheang shows, fed a taste for Chinese furniture, porcelain and clothes among women of the middle classes. At once a celebration of Britain’s greatness (based on nostalgia for a similarly once great, but now corrupt Chinese empire) and an assertion of class intentions, the possession of Chinese objects by wealthy white women rested on ownership of high quality objects whose craftsmen were associated, through time and geography, with the greatness of China’s past.[38]

At the same time, the writing of art historians such as Laurence Binyon (1869–1943), Stephen Wootton Bushell (1844–1908) and others, was helping to define Chinese objects as “art”, momentum which was maintained into that century by the likes of the translator and Sinophile Arthur Waley (1889–1968) and by scholars of its material culture at the Victoria and Albert Museum such as Bernard Rackham (1877–1964) and William Bowyer Honey (1891–1956), to name only a few.[39] At the same time in the 1910s, institutions such as the Burlington Fine Arts Club held exhibitions of Chinese “art” which included indigenous Chinese examples of jade, bronze, porcelain, furniture and other types of objects which were not popularly known within Western culture.[40] Similar trends were also evident in the United States. Declining anthropological interest in more recent objects produced in China, owing to growing interest in so-called “Primitive Cultures” coupled with anthropology’s linguistic turn, further drew the discipline away from the more recently produced Chinese objects.[41]

In this period, the quality of Chinese objects available in the West also increased. On-going railway building in the early-twentieth century unearthed some very early funerary objects, such as tomb figures and early oracle bones. Formal archaeological digs—first promulgated by adherents such as Edouard Chavannes (1865–1918) and later taken up by Western-trained Chinese such as Li Chi (1896–1979)—also helped to release a flood of objects.[42] Not only did the digs aid European experts in re-evaluating Chinese art. They also helped Chinese “art historians” themselves who, grappling with the place of China and Chinese objects in the world, came increasingly to value such early tomb art as “art”.[43] To European interpreters, the “discoveries” revealed Japan’s debt to China and, in turn, contributed to their re-evaluation of Chinese objects as art in many senses superior to Japanese productions (now seen as derivative of China). Indeed, to some Western art critics, the “unchanging” traditions of the East offered creative counterpoint to the now-hackneyed art forms of the West which had in their view become irrevocably corrupted by modernity and the machine. By the twentieth century, more and more Chinese objects were becoming available in the West thanks to China’s internal instability. Imperial China’s collapse in 1911 released yet more objects into the European and North American art worlds. The country plunged into chaos, a situation eagerly taken advantage of by competing warlord factions, the Communist Party Nationalists and, of course, the invading Japanese. In these tumultuous decades, Chinese intellectuals and officials attempted to present new national narratives of Chinese art (meishu 美術) through government-sponsored exhibitions of the newly nationalised imperial art collection and through its writing, again with important impacts on Western connoisseurship.[44]

China on Display, the 1937 Exhibition of Chinese Art

War and official exhibitions, recontextualisation of Chinese objects and their greater availability outside China, laid the intellectual and material basis for the Exhibition of Chinese Art, held in New Zealand in 1937. In Europe and North America, the period from the early twentieth century to the 1930s had witnessed something of a shift in the objects admired by collectors. In the early twentieth century, British collectors principally valued Chinese paintings. From the 1920s, attention increasingly turned to Chinese objects (porcelain from the 1920s and ritual bronzes and jades by the 1930s), a trend strongly reflected in the 1935–36 International Exhibition of Chinese Art.[45]

This unprecedented exhibition involved the loaning of over 850 objects by the Chinese Government for a landmark display of Chinese art in Britain. Its importance lies in demonstrating how Chinese objects were coming to hold different values not only in China but also in Europe, processes reinforcing, moreover, the recontextualisation of the different social lives of objects. Before and after the London exhibition, the Chinese Government displayed the ex-imperial artefacts in China. It did so in part to assuage doubts about the sagacity of sending such valuable “national treasures” (guobao 國寶) overseas. But more importantly, as exemplars of “national treasures”, the Preliminary Exhibition of Chinese Art (1935) literally provided an object lesson to its people, of China’s new place in the world. Transported to Europe, the objects symbolically represented the nation, serving also “as a diplomatic tool with which to gain support for its war against” the Japanese invaders. The arrangement of both the Preliminary Exhibition of Chinese Art (1935) in Shanghai and its later European display demonstrates the very different approaches to the valuation of art in China and Europe. At the Shanghai exhibition, the chronological arrangement of objects by category (bronze; porcelain; calligraphy/painting and miscellaneous, including jades, ancient books, and furniture) emphasised the progression of Chinese art for visitors already familiar with Chinese history and culture. By contrast, at the later International Exhibition of Chinese Art, the British laid great stress on the importance of ceramics and dynastic progression, moving visitors from familiar items to unfamiliar and including even a hall space of objects exemplifying “European tastes”.[46] A similar focus on ceramics and of narrative development about the objects accompanied the 1937 New Zealand exhibition.

The New Zealand Exhibition displayed over 360 objects and travelled to the four major centres of the country in the first six months of 1937.[47] It represented the culmination of a series of New Zealand exhibitions of Chinese and Japanese art objects organised and curated during the uneasy 1930s by Captain George A. Humphreys-Davies (1880–1948).[48] Humphreys-Davies, honorary curator of the Oriental Collections at the Auckland War Memorial Museum, was one of the foremost New Zealand collectors of East Asian decorative arts for his time and place.[49] The 1937 exhibition was particularly significant not only for its unprecedented and ambitious scope, but also for the attention it received from both the wider public and members of the art cognoscenti. Firstly, Exhibition organisers portrayed the objects on display as representative of “Chinese art”, a category of material culture probably relatively unfamiliar to most contemporary New Zealanders.[50] Much discussion of the Exhibition in newspapers, public talks and in the catalogue itself drew conclusions about Chinese culture and society from the material displayed in the Exhibition. In their analysis, writers positioned objects as metonymic ciphers for an abstract “China”, rather than as exemplars of a particular “school” or art movement as would be apparent in any exhibition of Western art. Secondly, the Exhibition included many pieces loaned by renowned European institutions and affluent private collectors. Their participation lent the display an air of prestigious authenticity, ensuring that both the event and the objects on show received close attention from a broad spectrum of New Zealand society. Thirdly, although in some respects the Exhibition confirmed existing stereotypes of “China”, in others it effected significant changes in the understanding of Chinese “art” in the Dominion. Interpretation and valuation of the objects occurred within a framework of Western cultural and aesthetic discourses, but these discourses were in turn shaped by the appearance of objects which had hitherto had only a relatively brief history of public display in Western societies. This instance of encounter with heretofore unknown elements of élite Chinese material culture reflected a broader trend in Western societies initiated through the processes described above and through the gradual re-evaluation of the taxonomic categories used to describe Chinese material culture. Indeed, the 1937 Exhibition reveals in microcosm much about the wider discourses about China circulating in New Zealand at this time. Significantly none provoked debate about the remnant Chinese population living in New Zealand.[51] Instead, it fed into a growing awareness of, and sympathy for, the plight of China under imperial Japanese aggression. In the 1930s a series of New Zealand writers travelled to China, reporting back favourably on the progress of, in particular, communism.

The interviews of Mao Zedong by journalist James Bertram (1910–93) later formed the corpus of the Great Helmsman’s political sayings, and led to a lifelong interest in China’s welfare. Robin Hyde (1906–39), writer and poet, composed arguably her greatest works as a result of travel through war-torn China. Rewi Alley (1897–1987) went on to found the Association of Chinese Industrial Cooperatives and become a prominent support of communist China.[52] Cast in this light, the collection of Chinese objects in the twentieth century represents a hitherto unacknowledged aspect of New Zealand’s engagement with Chinese material culture.[53] It also fills a historiographical gap in writing on the history of New Zealand art and exhibitions. Both areas of scholarship have primarily been concerned with the development of European art traditions in a New Zealand context as well as, in particular, the relationship between Māori and European art and display.[54] While several authors have explored the collection and exhibition of Japanese artworks, the field of Chinese art remains undeveloped.[55] The present article therefore helps to answer a question posed by Duncan Campbell, who asks what the “mute but eloquent surfaces of” Chinese objects can tell later historians of the experience of Sinophilia and Sinophobia in early-to-mid twentieth-century New Zealand.[56]

At an artistic level, the 1937 Exhibition represented a fascinating rejection of, but also an implicit enthronement of, European ideals of art and connoisseurship; a somewhat contradictory statement about New Zealand art and nationhood certainly, but a testimony to the multivalency of objects and the narratives woven around them. Many New Zealand artists and writers of the 1930s, art historian Francis Pound states, were straining “to cut free at once from the colonial past and from a maternal England”. Yet they also, as Pound notes, drew selectively from British and international movements, without necessarily acknowledging so.[57] The use of Chinese art objects fulfilled the desire of many artists, Beaglehole included, to sever New Zealand’s links with the colonial past and its traditions of British imported art. The holding of such an important international exhibition, able to rival those of Britain or North America, reinforced to some the growing national independence of New Zealand. But at the same time, the concept of an exhibition of this nature borrowed from British precedents; the appreciation of the objects followed European and North American conventions; indeed, the authority of the objects on display derived from their possession by eminent members of European royalty and wealthy. Humphreys-Davies’s intention was undoubtedly to organise an exhibition to rival those of Europe and serve as a statement of the Dominion’s cultural sophistication. Another interpretation was represented by the artist T.A. McCormack (1883–1973). For him, engagement with Chinese objects represented an alternative non-European artistic inspiration. Still another reading—evinced at a more popular level—was the collapsing of the 1937 Exhibition into existing discourses about chinoiserie.[58] The next sections examine the Exhibition’s presentation and reception.

Networks of Collecting and the 1937 Exhibition

Meticulous organisation was required to mount an exhibition which The Times anticipated “should prove to be the most important display of Oriental art ever held in the Antipodes”.[59] Humphreys-Davies, the wealthy New Zealand sheep farmer responsible for curating it, had spent considerable time laying the groundwork for it over the preceding years, most notably during a trip to Britain he undertook in 1936. The delicate issues of securing objects for loan had to be negotiated; then, insurance secured; packing overseen; a shipper agreed upon, not to mention a catalogue written, talks given and reports drafted to satisfy the ever-present demands of mindless bureaucratic minutiae (replete with the usual quibble about a few pounds, pence and shillings not accounted for).[60] Surviving letters, and the exhibition catalogue itself, demonstrate Humphreys-Davies’s familiarity with many of the main collectors and curators of Chinese art in North America and Europe. As in Humphreys-Davies’s case, access to this network demonstrates the power of Chinese objects—and knowledge of them—to effect the upwards social trajectory of their owners.

From surviving evidence, it seems Humphreys-Davies’s collection and his expertise in Oriental art facilitated social mobility. The son of a surveyor/auctioneer, Humphreys-Davies served as a lower-ranking officer in the British Army and, later, Royal Air Force. His developing interest in Chinese art most probably owed itself to the interests of his father in art and exposure to many of the exhibitions mentioned above. Collecting was also a passion he shared with his wife, Ethel, the daughter of a wealthy mining engineer from San Francisco. Ethel’s wealth and social connections would inevitably have helped their shared passion for collection. Certainly, Humpreys-Davies’s growing expertise appears to have given him entrée, or at least eased his passage, into the cultured life of the very rich and famous.[61]

By the 1930s, in negotiating the loan of items for the exhibition, Humphreys-Davies was rubbing shoulders with royalty and the seriously wealthy. There are warm letters exchanged with George Eumorfopoulos (1863–1939), whose outstanding collection of Chinese objects, paintings and sculpture formed the basis of the holdings on that region’s art at the Victoria and Albert and British museums. The two took tea when Humphreys-Davies visited England in 1936 to organise the collection and continued to correspond on progress of the exhibition.[62] In London, Humphreys-Davies also met with the Directors of the Victoria and Albert Museum, which had recently acquired many of Eumorfopoulos’s Chinese collection.[63] Both the institution and the individual loaned objects. Eumorfopoulos loaned four objects to the 1937 exhibition: two Song dynasty 宋 (960–1279) porcelains (a bowl and a water-pot) and two vases, one a remarkably rare Tibetan piece with Sanskrit inscriptions dating from the fifteenth century. The Victoria and Albert Museum, its Chinese holdings recently swollen by acquisition of large parts of Eumorfopoulos’s collection, lent eight items (ranging from jars to blue and white ware).

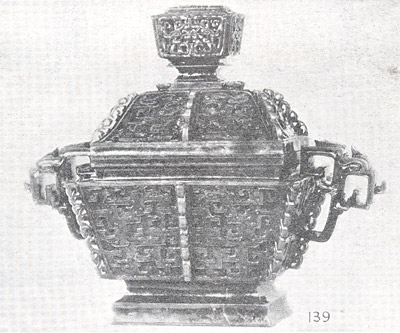

Many of the objects lent by European collectors for the 1935–36 International Exhibition of Chinese Art also made their way to New Zealand. Over forty pieces exhibited in New Zealand came from the collection of the late Charles Rutherston (1866–1927) through a loan by his widow and Mrs Powell, Rutherston’s daughter. This material ranged from pendants to porcelain and celadon. Several other significant collectors, such as the pre-eminent dealer and collector C.T. Loo (1880–1957), who lent 82 objects (principally bronzes and jades), also contributed.[64] Some three dozen objects from the collection of Humphreys-Davies and his wife, principally porcelain and celadon, along with several jades, were shown, while other New Zealand-based collectors lent single items or, in the case of Mrs M.G. Moore, jades and lacquer-ware. By far the greatest proportion of art were objects, a reflection of Humphreys-Davies’s overriding passion and the then overwhelming popularity for such forms of art.[65] Only nine Chinese paintings were exhibited. Six (one Yuan 元, 1271–1368, and five Ming 明, 1368–1644, landscapes) came from the collection of A.W. Bahr (1877–1959), the son of a Scottish father and Chinese mother who was raised in Peking. Three other paintings came from Hans Richter of Hong Kong.[66] Only two “stand alone” examples of calligraphy (that is, excluding seals or inscriptions on objects) were exhibited (Figure 1).

The Display of the 1937 Exhibition

The exhibition attracted “large audiences” when it opened at the Auckland War Memorial Museum on 15 January 1937.[67] The New Zealand Herald ran several articles on the exhibition at Auckland. “[T]his collection”, it declared, “… bewildering in its variety and astonishing in its richness and rarity … is not an exhibition that will disclose itself to a casual glance, but it is one that will abundantly repay careful and thoughtful study”.[68] The description at once hinted at the need to seriously engage with Chinese art, but also conveyed a sense of its unknowable nature, a sense of mystery traditionally associated with European representations of China.

To help visitors interpret the exhibition, lecturers and the guidebook stressed its unique didactic opportunities for both aficionados and amateur lovers of art to extend their knowledge beyond the Western tradition. Humphreys-Davies, for one, lectured “to the groups of students and school children who visited the gallery in large numbers, and also was occupied most of the day giving information to any visitor who asked for it”.[69] Attending “for many hours at the museum”, he opened cases and gave “visitors the privilege of turning over pieces of jade and metalwork in their own hands,[70] while he related that this bronze plaque had adorned a Tartar warrior’s horse and that golden bird the head of an empress. Modestly and simply,” the writer to the editor concluded, “Captain Humphrey-Davies has opened a new world of thought and knowledge to many people” and “deserves the community’s gratitude”.[71] Humphreys-Davies prided himself on the many working class men attending the exhibition, giving away, as he noted on another occasion, “large numbers” of the catalogue “to those who looked as if they could not afford” its 2/- price.[72] This facet of the exhibition merited mention by several other authors. “One noticeable feature”, noted the anonymous reviewer of its Christchurch leg, “… was the number of workers who came many times; it certainly was not an uncommon sight to see men in dungarees side by side with students, many of whom came frequently to make drawings of the pottery and bronzes”.[73]

Emphasis on the social purpose of art, in particular its relevance to the working classes, reflected a convergence of several historical trends. First, with the Great Depression’s effects biting hard in the colony, the lavishing of money on such an event could easily have been viewed as frivolous. Stressing its appeal to the working class made sound political sense and attempted to deflect any potential criticism. Second, the conscious attempt at “educating” the public in different art traditions chimed with contemporary lamentations about the quality of public art then shown. Humphreys-Davies himself generated considerable sparks when he claimed, somewhat unwisely perhaps, that much of New Zealand’s art galleries exhibited second-rate British artists largely shunned by those of taste in Britain.[74] The socially useful aspects of art, in particular, drew comment from several authors. An editorial of the Dominion Post echoed the curator’s hopes, noting that the display of 3000 years of art will cause “Mr. John Citizen” to lose “a large part of his conceit” about Western civilization.[75] Dr C.E. Hercus, Chairman of the Carnegie Foundation Committee responsible for granting funds towards the exhibition, claimed that in New Zealand “the artistic side of the life of its people was relatively undeveloped. Some idea of the essential character of art would be given to this exhibition, which would encourage young people to express themselves in some form of material, and so solve the problem of leisure”.[76] In other words, to these writers, art fulfilled a distinct social function by harnessing the otherwise errant energies of youth and the working classes towards consideration of higher things. It also sowed the seeds of national art appreciation among the New Zealand public.

Ironically, that attempt at creating a visually literate national public appreciative of fine art, relied strongly upon the British context of the objects’ owners (explored in the next section) and British expertise. The exhibition catalogue, along with the requisite descriptions and pictures of the exhibited objects, featured three essays, all from leading British academics. They expounded upon various topics deemed to constitute Chinese “art”: Marion Thring, Lecturer, Victoria and Albert Museum, on “Line Form and Colour in Chinese Art”; S. Howard Hansford on “Ceramics under the Han, T’ang and Sung Dynasties”.[77] The lengthiest, by W. Perceval Yetts (1878–1957), Professor of Chinese Art and Archaeology at the University of London, placed objects from the exhibition into an overarching teleological narrative. Yetts’s article traces the evolution of ancient “Chinese civilisation” from its prehistoric ancestor, Sinanthropos pekinensis, through to the Song dynasty. Significantly, his narrative leaps from the Song, often regarded as a period of great technological acceleration in Chinese history,[78] to the onset of “scientific excavation in China” in Anyang in 1920 by Western archaeologists. Yetts summarily dismisses the intervening time as insignificant: “during the five hundred years which followed the Sung, no very notable advance was made in Chinese archaeology”.[79]

Here, Yetts presents Western archaeological and anthropological knowledge as the founding narrative from which he speaks as an authority on Chinese “civilisation”, enabling him to imbue the sequence of material progression with a racialised subtext that correlates the perceived level of material culture with hierarchical notion of race. This is evident in his evaluation of bronzes taken from the Zhou 周 dynasty (1045–256 BCE) tombs in Henan 河南 province. For Yetts, “while they show a continuance of the Shang-Yin tradition [1600–1046 BCE], there is a perceptible coarsening of the finer qualities that distinguish their prototypes. This accords with the belief that the Chou were less cultured than the people they conquered”.[80] For Vishakha Desai, the use of a narrative grounded within Western epistemological traditions to explain Chinese material culture indicates that Asian objects in a Western context “carry with them not only assumptions about the culture for which they were produced, but also … the values accorded to them by the culture in which they are now located.”[81]

An analysis of the exhibition space and the photographic techniques used to represent objects reinforces the hierarchical narrative influencing their visual display. Photographs of artefacts from the catalogue attempted to impose a “rational taxonomy of rule-governed possession”.[82] Categorised according to their physical appearance and material composition, they are photographed together with like pieces, a system used to group the objects textually in the catalogue and which was also evident in the 1935–36 International Exhibition of Chinese Art in London. In the 1937 exhibition catalogue, objects appear with brief explanatory statements about their cultural production. Such a taxonomic approach lends the exhibition catalogue an ethnographical air. Humphreys-Davies sought to value and present objects according to “objective” scientific and archaeological criteria, meanings in part derived from their use-value and period of manufacture (but, it must also be noted, according to the beauty of their design).[83] Jack Clifford has argued that such an approach to the understanding of exotic objects demonstrates

how collections, most notably in museums, create the illusion of adequate representation of a world by first cutting objects out of specific contexts (whether cultural, historical, or intersubjective) and making them “stand” for abstract wholes … . Next a scheme of classification is elaborated for storing or displaying the object so that the reality of the collection itself, its coherent order, overrides specific histories of the object’s production and appropriation.[84]

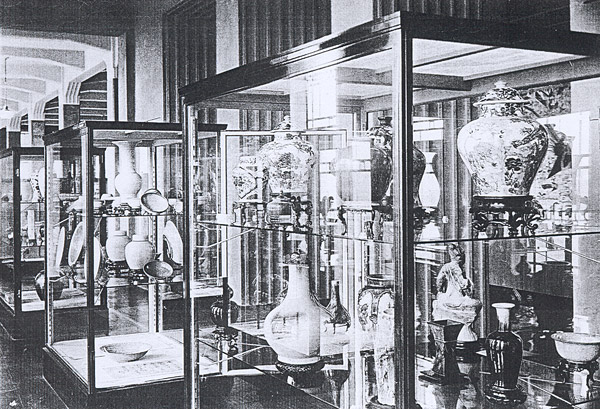

The influence of this taxonomic approach is further evident in the exhibition’s spatial layout. Photographs of its display at the National Art Gallery and Dominion Museum (now Te Papa Tongarewa/The National Museum of New Zealand), Wellington, show items arranged in glass cases separated into categories by medium, a presentation which throws them into sharp relief against the unadorned walls of the museum space (see Figure 2). No labels appear to be provided. The only markers are red tags which indicate their previous appearance at the landmark 1935–36 exhibition and which proffer further evidence of the newly reconfigured social lives of the objects. Instead, a number below the object refers the viewer to the catalogue, which, as noted, provides no history of the individual items save for basic details of type, medium, and approximate period of manufacture—also a reflection of the technically based taxonomical approach to the collection. Such a spatial arrangement encourages viewers to see the objects as representative, yet exclusive, examples of a class of “Chinese art”. By setting objects with like objects, viewers can evaluate their relative aesthetic merit, but divorced largely from the social and cultural processes of their production.

The Popular Reception of the 1937 Exhibition

The 1937 exhibition appealed to a broad audience. Its display, guidebook and lectures certainly aimed to direct interpretations of the objects, and to extol the lofty ideal of improving national aesthetic tastes. Another important manner in which the objects were presented was in relation to their owners. As well as the Guidebook, local newspapers, in particular, carefully enumerated the many European aristocratic collectors, as well as wealthy North Americans, who had loaned their valuable pieces for the display. This enumeration was important because it gave a cultural context in which otherwise unfamiliar objects could be assessed and valued. The value of such an exhibition, the message went, derived from the displayed objects’ ownership by wealthy and prominent Europeans and North Americans, and from the prior exhibition of certain objects in Britain.

Figure 3

The most popular and commented-upon object in the exhibition, Queen Mary’s “Jade Casket”.

Figure 4

A jade buffalo, possibly obtained during the sacking of Yuanmingyuan in 1860. Figures 3 and 4 from: Captain George Humphreys-Davies, ed., An Exhibition of Chinese Art, Including Many Examples from Famous Collections, Exhibited in New Zealand (Auckland: N.Z. Newspapers Ltd., 1937), no page.

Newspapers made much of the background of the private collectors associated with the exhibition, many of whom were titled members of the English gentry. As a case in point, every newspaper which covered the exhibition mentioned a “delightful” jade casket loaned by Queen Mary (1867–1953, r. 1910–36) (Figure 3). Indisputably it was the most popular item in the exhibition. Its photograph appeared in all of the major metropolitan newspapers.[85] Dunedin’s Otago Daily Times, for example, praised Queen Mary for setting “a good example to other enthusiasts by lending an elaborately carved casket of dark green jade”.[86] Other writers devoted columns to the well-known names in London art circles, such as Eumorfopoulos, Oscar Raphael and Victor Rienacker, and members of the aristocracy such as Lady Patricia Ramsay (1886–1974), a granddaughter of Queen Victoria. They pointed out that New Zealanders were able to see objects seldom, if ever, displayed beyond such bastions of “Britishness” as the Victoria and Albert Museum.[87] Of the individuals mentioned, Eumorfopoulos’s loan of “a bulb bowl of the Sung dynasty” attracted comment because, as the Otago Daily Times informed its readers, the object was well-known in European art circles and, what was more, “is one of his favourites”.[88] Likewise, display of objects from the collection of well-known and respected Europeans with connections to New Zealand further helped to orientate visitors towards the value and quality of the objects on display. Lord Bledisloe (1867–1958), New Zealand’s popular Governor-General from 1930 to 1935, loaned two Wanli-era 萬曆 porcelain pieces. A jade buffalo, possibly obtained during the sacking of Yuanmingyuan in 1860—from the collection of Sir George Grey (1812–98), another former Governor (1845–53; 1861–68)—also received considerable attention due to its association with such a well-known political figure (Figure 4).[89]

Further helping to translate the value of these objects were red tabs attached to particular objects. These alerted visitors to those artworks which had previously appeared in “special exhibitions in European museums and galleries”, including “the great Chinese Exhibition held by the Royal Academy at Burlington House” in 1935–36.[90] Significantly, the narrative of most of the objects discussed omitted or only very briefly mentioned an object’s “social life” in China. Instead, in New Zealand, who had owned what objects, and where they were displayed, provided sufficient foundation for an evaluation of the objects themselves. Élite practices of collecting might still help in appraising an object’s value, but in New Zealand, it was now the British, not the Chinese elite, who effected this process.

Other interpretations of the exhibition harked back to older, feminised depictions of Chinese art associated with early periods of chinoiserie. Several articles on the exhibition appealed to the perceived special interests of women. Featuring strongly in these articles were the subjects of marriage customs, “domestic life”, handicrafts and the genteel aesthetic pursuits of Chinese people, coupled with fashion articles on chinoiserie. The last focused on the social aspects of the exhibition, such as the assertion in the “Every Woman’s Pages” of The Weekly News of 3 February 1937 that “it is in the porcelain section that most women will delight, for the old glazes and beautiful designs are a joy to behold”.[91] Another article breathlessly declaimed that the 1935–36 International Exhibition of Chinese Art held in London had stimulated new shoe fashions in Auckland to reflect “the Chinese influence”.[92] The “Woman’s World” section of the New Zealand Herald listed the wives and ladies entertained to tea, whilst remarking dubiously of the exhibition itself that in it “is collected the quaintness, the grotesqueness, and the simple beauty of Chinese art”.[93] The Herald’s description echoes the late eighteenth century European reassessment of chinoiserie and Chinese customs as something somehow monstrous, uncouth and totally unlike anything in the West. Accordingly, the objects here become reducible not to the creativity of an individual artist, but to the perception of a grotesque simplicity.

Reception Among New Zealand Artistic Circles:

Poetry and Painting

Elsewhere, the 1937 exhibition generated vigorous debate and gave creative momentum to the New Zealand art community. New Zealand’s self-proclaimed art cognoscenti responded in generally positive yet complex ways, with many approaching the exhibition from the perspective of chinoiserie and japonisme as popular styles of aesthetic expression already prevalent in inter-war New Zealand. In other ways, attempts at aesthetic appreciation of Chinese objects hinted at a different debate underpinning the practice of art in New Zealand: the question of “tradition” and its application in a colonial society in which several art-leaders were seeking to find a distinctly unique and “national” voice, one drawn also from non-Western traditions including Māori and Asian art.[94]

If the subtitle of the journal Art in New Zealand, founded in 1928 and running until 1947, chronicles the nationalist desire of artists in the Dominion to establish A Quarterly Magazine Devoted to Art in its Various Phases in Our Own Country, its pages express the fascination with Chinese and Japanese culture which informed some artistic practice in inter-war New Zealand towards that nationalist goal. Interest in alternatives to European traditions was mentioned by literary biographer E.H. McCormick (1906–95). Recalling his student days at Victoria College (University of New Zealand), McCormick noted the “cult of eclectic orientalism” which held sway in that period. Salvaged Japanese prints, he recalled, would be “mounted on strips of fabric and hung over black divans in dimly illuminated studio-bedsitters” while: “Respectable virgins ransacked the Chinese shops in Wellington’s red-light district for rice bowls and fish plates of approved design.”[95] Placed in this context it is unsurprising that the 1937 exhibition appears in Art in New Zealand as an important, but by no means singular, instance of appreciation for Eastern aesthetics that stretched to the search for new ways of enjoying and engaging with non-European objects.

The journal carried three poems by J.C. Beaglehole. The first part of “Chinese Plate”[96] (an excerpt from its second section appears at the beginning of this article), records Beaglehole’s emotive, affective engagement with a painting of a fish which decorates the plate. In the poem, Beaglehole deftly leaps from contemplation of the artistic creation of the fish to the broad sweep of a Chinese landscape. The landscape, containing both himself and the fish, embodies the poet’s yearning for emotional release.[97] Longing for “… the great land, the wide plain and the mountains,/ the wild geese and the cranes, the cypresses/ shadowing leaf-strewn path and watched by moon”, the poet dreams himself into communion with the heroic figures of Chinese literature.[98] In the second part of the poem, its compression of time, places and objects and in its overwhelming sense of anxiety somehow perhaps foreshadows W.H. Auden’s (1907–73) dark sonnet-sequence drawn from his and Christopher Isherwood’s (1904–86) visit to war-torn China in 1938 and published as “In Time of War” (1939) in Journey to a War.[99] In the second part of the poem, Beaglehole imagines himself into the life-world of the tea-caddy he is handling, into the role of a Chinese literary scholar, as a means of escaping from the modern world where “the newspaper is full of the talk of war, stupidity, brutality, men’s unconscionable bitterness to men, politics and economic confusion”.[100]

Utilising natural phenomena as a metaphor for his inner feelings, Beaglehole employs a key figurative device in Chinese literature to express his wish to enter into the aesthetic world of Chinese material culture. Significantly, he selects an object, rather than a text, as the muse for his fantasy of aesthetic sublimation within a Chinese universe. As he turns the tea-caddy over and over in his hands, at one level, the exact meaning of “… the incised beautiful/characters, red and black I cannot read” is, of course, inaccessible. Yet, at another, the characters are multivalent, possessing a power not immediately apparent by their direct, linguistically translatable meaning. In her study of monumentality in medieval Cairo, Irene Bierman has shown that, even to the illiterate, the form, colour and materiality of writing possessed a power to communicate. Similarly, in Ming China, “[t]he importance of foreign scripts … was out of all proportion to the number of people who could read them.”[101] Even if scripts could not be read in the conventional sense, the importance of the role of text in governance, taxation, and communication was as apparent to Beaglehole as it was to Cairo’s illiterate.

Likewise, the allure of a foreign text to Ming scholars, as to a New Zealand scholar removed from that period temporally, geographically and culturally, lay in its exoticism. Indeed, the very linguistic inaccessibility and foreignness of the text forced Beaglehole to consider its form, “… the incised beautiful/characters, red and black I cannot read.” Such a process may have inadvertently drawn Beaglehole closer than he ever realised to the cultural practices of traditional Chinese calligraphic appreciation; to Confucian surety in the power of dot and stroke formation to harness the vital energy (qi 氣) that form characters not just evocative of the qualities of the artist but also which itself effect social and political change.[102] Reinforcing this interpretive avenue is the manner in which Beaglehole engaged with the object. By engaging with it as an entity capable of reflecting the emotional and creative projections of the self, Beaglehole seems to promulgate an aesthetic interpretation of Chinese objects centred on the psychological processes they can create in the individual, rather than any interpretation of them as an expression of discoverable realities about a foreign culture. This is significant if we consider Yanfang Tang’s analysis—however problematic and orientalised—of the differences between reading in Western and Eastern literature. For efferent reading in the Western tradition, notes Tang, “the reader’s primary concern is with what he will “carry away” from the reading—information, solution to a problem, perhaps an imperative for action”. In contrast, the elevation of aesthetic reading in Eastern literature prioritises “only what is experienced during the reading event”.[103] Thus, Beaglehole’s engagement contrasts the more common experience of Chinese objects in societies such as New Zealand, where aesthetic and scientific discourses competed to define the experience of exotic objects for the individual.

By no means did Beaglehole exhaust the Dominion’s artistic interpretation of Chinese objects. To New Zealand art writer, Edward C. Simpson, writing in 1938, “a painting has, in fact, a distinct racial character … its virtues are those of a particular people”.[104] Although placing Chinese painting on an evolutionary scale, Simpson nevertheless inverted traditional typologies by ranking it above the West. It warranted this place thanks both to the length of its art history, and because, he pointed out, “Chinese painting is more fully developed as an aesthetic language than any other kind of painting the world has known.”[105] Simpson also draws an analogy with Western music, said to function as the chief outlet for the “artistic genius” in the European context.[106] Musing in an opinion piece on the exhibition, “Kotare” (meaning Kingfisher in Māori) began by upholding all the very worst Anglo stereotypes of China, writing “somehow, it is not easy for the Briton to take China very seriously. It seems inextricably associated with vegetables and laundries and fantan and opium. The British mind instinctively finds something ridiculous in any way of life that differs from its own.” However, the author goes on to acknowledge that “China beat out of her long and chequered experience a scale of values and a conception of life and the universe that rank among the supreme achievements of the human mind”.[107] Significantly, however glorious they might be, these achievements lie in the past, a common trope in writing on China by Westerners in this period.[108] Although inverting the commonly drawn relationship between Western and Eastern art, both Simpson and Kotare nonetheless situated Chinese art along a timeline of development which is culturally and chronologically determined and, in this sense, evince the same concerns with race and “civilisation” informing the exhibition catalogue itself and, especially, those of Professor Yetts.

As already noted, Yetts considered the objects to hold the essence of Chinese civilisation—the “means for understanding a great and ancient race”.[109] Extending this notion, the Dominion Post editorial picked up Yetts’s statement that “for New Zealanders, Chinese art may be said to offer a special interest, because of certain similarities with Maori ornament” and that “these considerations should quicken the interest of the lay citizen in the unique exhibition now in Wellington”.[110] The intent of these statements is unclear, as both authors failed to take up the comparison further. Several possibilities, however, suggest themselves. The comments could refer to the quest for origins which so obsessed European—as well as many Māori—writers and archaeologists.[111] In a related fashion, it could equally refer to the practice of arranging the cultural products of different societies within a distinctive archaeological taxonomy. In this case, it may have invited comparison between “Stone Age” jade pieces from China’s distant past and pre-contact Māori productions in pounamu (jade), which many European observers viewed as representative of “Stone Age” development.[112] Possibly, too, the appeal to comparison may well refer to the developing interest of artists in New Zealand in Māori motifs and subject matter. Such an appeal could easily be incorporated under the expansive definition of the Western art movement known as primitivism. This movement, growing beyond its early parameters to incorporate anything beyond the west, as Francis Pound notes, “opened up the very possibility of non-Western arts being admired in the West”.[113]

For the English-born artist and critic Christopher Perkins (1891–1968), who resided at various times in New Zealand, engagement with China was particularly opportune. “Just at the moment when we are losing our poise under the impact of the mechanism and vulgarity of this age”, he declared, “come sages from the East to teach us a new technique of the spirit”. However problematic his opinion might be, Perkins at least engaged with aspects of the aesthetics of China, emphasising the desire in Chinese painting to depict the “inner nature of things”, of a tradition concerned less with visual representation of reality as in the West than with conveying “the feel of their surfaces and the spirit of their movement”.[114]

Moving now from word to image, the artwork of T.A. McCormack may reveal something of the influence of the 1937 exhibition on the aesthetic understanding of some New Zealand visual artists at that time. For art historian Anne Kirker, McCormack’s paintings, with their detailed brushwork and feel for the visual rhythm of landscapes, acknowledge “an influence which had hitherto been largely dormant amongst New Zealand painters this century, that of the Far East”.[115] McCormack himself viewed the 1937 exhibition as a major artistic influence, paying it several visits at its Wellington stage. For him, notes Kirker,

the four hundred pieces of jade, porcelain and painting confirmed the direction McCormack’s own work was taking. The Chinese-produced objects were vehicles of contemplation, poetic but not in the least rhetorical or romantic. The emphasis was on aestheticism and spiritual insight. In formal terms, McCormack came to appreciate more fully the power of the brush in Oriental expression and the concentration on essentials.[116]

McCormack also sought inspiration from Japanese traditions, to add to the impressionism he was already familiar with. McCormack’s contemporary, David Martineau, for example, compared the artist’s work, “Seascape”,[117] to the renowned wood-cut, “The Hollow of the Deep-Sea Wave off Kanagawa, Japan”, by the Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai 葛飾 北斎 (1760–1849).[118] For Kirker, however, aspects of McCormack’s work directly responded to the Chinese art exhibition, not simply his use of watercolour but more particularly his deft knowledge and control of brushwork. If so, it reflects the creative impact of display of Chinese material culture on the development of artistic expression of a major New Zealand artist.

Conclusion

The 1937 exhibition of Chinese art, held throughout New Zealand in the first half of that year, presented to the Dominion’s public a fascinating window into another culture’s artistic traditions. Taxonomically displayed, objects stood as a cipher for the culture which produced them. Yet official narratives about “Chineseness” were sometimes supported, sometimes sublimated by the active cultural and aesthetic engagement of the general public and art community. To some, the display appealed to existing gendered notions of feminine interest established by the entrenched vogue for chinoiserie; to many, the objects acquired value through their association with wealthy European collectors and their participation in previous exhibitions held in the cultural capital of Europe. To others of perhaps a more artistic bent, the Chinese objects promised to breath life into the near-moribund form of twentieth-century Western artistic life. They provided an aesthetic and technical inspiration for art practice, encouraging an emotional and imaginative engagement with the self and a didactic opportunity designed to raise the artistic education of New Zealand’s artistic and lay public alike. Whatever its objects’ polysemantic meaning, the exhibition evinces the dynamic social lives of objects removed from their cultural contexts and set in motion in wholly new regimes of value. The exhibition also strongly suggests to scholars the need to reassess our understanding of the fictional chasm that yawns between Eastern and Western cultures, perhaps even to move towards scholarly accommodation of the many hybrid cultural movements that have flourished within the history of global trade. In the case of New Zealand, this requires a drastic rethink of the simplistic binary of bi-culturalism (Māori and European) which reigns as the orthodoxy in the writing of New Zealand’s past, if not at least in its art historical traditions.

James Beattie

History Programme

University of Waikato

New Zealand

jbeattie@waikato.ac.nz

Lauren Murray

Summer Scholar

University of Waikato

New Zealand

lmurray.mlr@gmail.com

The authors would like to thank the following individuals and institutions for their help: Duncan Campbell and Richard Bullen, and the anonymous peer reviewers, for commenting on earlier drafts; the advice of Dr David Bell, Dr Kirstine Moffat, Associate Professor Mark Stocker and Dr Donald Kerr, University of Otago, Professor Nick Pearce, University of Glasgow and, as always, Professors Craig Clunas and John M. MacKenzie for their scholarly inspiration; Public Records Office, Kew; Martin Collett and Simona Traser, Auckland Museum/Tamaki Paenga Hira; Jennifer Twist, Becky Masters and Ross O’Rourke, Te Papa/National Museum of New Zealand; Moira White, Otago Museum; Seán Brosnahan, Otago Settlers Museum. Lauren Murray's research undertaken for this article was supported by a “Summer Scholarship” in History at the University of Waikato from December 2009 – February 2010. For his research, James Beattie was supported by a Vice-Chancellor’s Research Award, University of Waikato.

1 J.C. Beaglehole, “Three Poems of Escape,” Art in New Zealand 8.2 (1935): 91–3, at p.92.

2 Craig Clunas, Art in China (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), p.9.

3 Craig Clunas, “Oriental Antiquities/Far Eastern Art,” in Foundations of Colonial Modernity in East Asia, ed. Tani E. Barlow (Durham: Duke University Press, 1997), p.418.

4 Amiria Henare, Museums, Anthropology and Imperial Exchange (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), p.2.

5 Arjun Appadurai, “Commodities and the Politics of Value,” in Interpreting Objects and Collections, ed. Susan M. Pearce (London: Routledge, 1994), p.83.

6 Susan M. Pearce, “Museum Objects,” in Interpreting Objects and Collections, ed. Pearce, p.9.

7 Pearce, “Museum Objects,” p.9.

8 Christopher Tilley, “Interpreting Material Culture,” in Interpreting Objects and Collections, ed. Pearce, p.72.

9 Appadurai, “Commodities and the Politics of Value,” pp.76–91.

13 Pearce, “Introduction,” p.4.

14 Steven Conn, “Where is the East? Asian Objects in American Museums, from Nathan Dunn to Charles Freer,” Winterthur Portfolio 35.2 (2000): 157–73, at p.160.

15 S.A.M. Adshead, Material Culture in Europe and China, 1400–1800: The Rise of Consumerism (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1997); Robert Finlay, “The Pilgrim Art: The Culture of Porcelain in World History,” Journal of World History 9.2 (1998): 141–87; Touraj Daryaee, “The Persian Gulf in Late Antiquity,” Journal of World History 14.1 (2003): 1–16, at p.7.

16 Note, Hilary Young, “Manufacturing Outside the Capital: The British Porcelain Factories, Their Sales Networks and Their Artists, 1745–1795,” Journal of Design History 12.3 (1999): 257–69. An entertaining discussion of the accidental discovery of porcelain manufacturing in Europe is provided by Janet Gleeson, The Arcanum: The Extraordinary True Story of European Porcelain (London: Bantam, 1998).

17 Finlay, “Pilgrim Art,” p.187.

18 Oliver Impey, Chinoiserie: The Impact of Oriental Styles on Western Art and Decoration (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977), p.10.

21 David Porter, Ideographia (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001), p.135.

22 Porter, Ideographia, p.135.

23 Jonathan D. Spence, To Change China: Western Advisers in China, 1620–1960 (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1980); Richard E. Strassberg, “War and Peace: Four Intercultural Landscapes,” in China on Paper: European and Chinese Works from the Late Sixteenth to the Early Nineteenth Century, ed. Marcia Reed and Paola Demattè (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2007), pp.104–37.

24 Beth Kowaleski-Wallace, “Women, China, and Consumer Culture in Eighteenth-Century England,” Eighteenth-Century Studies 29.2 (1995/1996): 153–67.

25 Jonathan D. Spence, The Chan’s Great Continent: China in Western Minds (London: W.W. Norton, 1998).

26 On which, see: Geremie R. Barmé, “The Garden of Perfect Brightness, A Life in Ruins,” East Asian History 2 (1996): 111–58; Wong Young-Tsu, A Paradise Lost: The Imperial Yuanming Yuan (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2001). On the neighbouring gardens, see: Vera Schwarcz, Place and Memory in the Singing Crane Garden (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008).

27 A phrase used by Arjun Appadurai to describe “complex periodical events that are removed in some culturally well-defined way from the routines of economic life. Participation in them is likely to be both a privilege of those in power and an instrument of status contests between them”. Appadurai specifically mentions art auctions as a sub-category of such events. Appadurai, “Commodities and the Politics of Value,” p.87.

28 James L. Hevia, “Loot’s Fate: The Economy of Plunder and the Moral Life of Objects From the Summer Palace of the Emperor of China,” History and Anthropology 6 (1994): 319–45, at p.324.

29 Hevia, “Loot’s Fate,” p.324.

30 Craig Clunas, “China in Britain: The Imperial Collections,” in Grasping the World, ed. Claire Farago and Donald Preziosi (Burlington: Ashgate, 2004); Impey, Chinoiserie; Hevia, “Loot’s Fate”; Nick Pearce, “Soldiers, Doctors, Engineers: Chinese Art and British Collecting, 1860–1935,” Journal of the Scottish Society for Art History 6 (2001): 45–52.

32 Hevia, “Loot’s Fate,” p.326.

33 Anna Jackson, “Art and Design: East Asia,” in The Victorian Vision, ed. John M. MacKenzie (London: V&A Publications, 2001), p.310.

34 John M. MacKenzie, “Empire and the Global Gaze,” in The Victorian Vision, ed. MacKenzie, p.259.

35 A useful summary of these debates is provided in: Qin Shao, “Exhibiting the Modern: The Creation of the First Chinese Museum, 1905–1930,” China Quarterly 179 (2004): 684–702, at pp.686–90.

36 Anna Laura Jones, “Exploding Canons: The Anthropology of Museums,” Annual Review of Anthropology 22 (1993): 201–20; Conn, “Where is the East?”

37 Clunas, “China in Britain,” pp.463–71. As a contrast, note the fascinating article by Ronald J. Zboray and Mary Saracino Zboray, “Between “Crockery-dom” and Barnum: Boston’s Chinese Museum, 1845–47,” American Quarterly 56.2 (2004): 271–306.

38 Sarah Cheang, “Selling China: Class, Gender and Orientalism at the Department Store,” Journal of Design History 20.1 (2007): 1–16.

39 See S.W. Bushell, Chinese Art, 2 Vols (London: Victoria & Albert Museum, 1914); Laurence Binyon, The Flight of the Dragon: An Essay on the Theory and Practice of Art in China and Japan (London: John Murray, 1953 [1911 original edition]). Also, Clunas, “China in Britain,” p.467.

40 Note, for example: “The Exhibition of Chinese Art at the Burlington Fine Arts Club-II. Notes on Jade,” The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 27.148 (1915): 158–68.

41 Conn, “Where is the East?” To this day, early dynastic productions, such as from the Shang 商 [1600–1046 BCE] and Qin 秦 [221 BCE–206 CE] remain in many museum collections as anthropological exhibits.

42 For an introduction to archaeology in China, see Corinne Debaine-Francfort, The Search for Ancient China (London: Thames & Hudson, 1999).

43 Guo Hui, “Writing Chinese Art History in Early Twentieth-Century China” (PhD diss., Leiden University, 2010).

44 Guo, “Writing Chinese Art History”; Jeanette Shambaugh Elliott with David Shambaugh, The Odyssey of China’s Imperial Art Treasures (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2005), pp.56 passim.

45 Basil Gray, “The Development of Taste in Chinese Art in the West, 1872 to 1972,” Transactions of the Oriental Ceramic Society 39 (1974): 19–50.

46 Guo, “Writing Chinese Art History,” pp.173–213 (quote, 180).

47 Captain George Humphreys-Davies, ed., An Exhibition of Chinese Art, Including Many Examples from Famous Collections, Exhibited in New Zealand (Auckland: N.Z. Newspapers Ltd, 1937), p.i.

48 Gilbert Archey, Guide to the Exhibition of Chinese and Japanese Art, July 4 to August 6 1932 (Auckland: Star Office, 1932); Humphreys-Davies, Guide to the Exhibition of Chinese Art, 1935–1936 (Auckland: no publisher, 1936).

49 Humphreys-Davies was heavily involved with the organisation of exhibitions of Chinese objects at the Auckland War Memorial Museum in 1932, 1933 and 1935, each time lending many objects from his personal collection, giving lectures, and editing the exhibition catalogues.

50 Humphreys-Davies, for instance, also lent material for a more limited display of Asian art in Dunedin. R.N. Field and Marion Field, “Otago Art Society’s Annual Exhibition,” Art in New Zealand 8.2 (1935): 93–96, at pp.94–5. Three previous displays of Chinese art took place in New Zealand, the first, in 1932, principally of Ming and Qing Chinese porcelain exhibited alongside Japanese art; second, in 1933, early Chinese ceramics; third, in 1935–36, of exclusively Chinese objects, mostly ceramics and bronzes. See Humphreys-Davies, Guide to the Exhibition of Chinese Art, 1935–1936 (Auckland: Auckland War Memorial Museum, 1935).

51 James Ng, Windows on a Chinese Past, 4 Vols. (Dunedin: Otago Heritage Books, 1993–1997); Julia Bradshaw, Golden Prospects: Chinese on the West Coast of New Zealand (Auckland: Shantytown Press, 2009); Lynette Shum, “Remembering Chinatown: Haining Street of Wellington,” in Unfolding History, Evolving Identity: The Chinese in New Zealand, ed. Manying Ip (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2003), pp.73–93.

52 On New Zealanders’ relationships with China in this period, note: Matthew Dalzell, New Zealanders in Republican China, 1912–1949 (Auckland: The University of Auckland New Zealand Asia Institute Resource Paper, 1995); James Bertram, The Shadow of a War: A New Zealander in the Far East, 1939–1946 (Australia: Whitcombe & Tombs; London: Gollancz, 1947); Bertram, Return to China (London: Heinemann, 1957).

53 It serves as a temporal continuation of the analysis presented by Brian Moloughney and Tony Ballantyne of the importance of Asia and its material connections in nineteenth-century southern New Zealand. Brian Moloughney and Tony Ballantyne, “Asia in Murihiku: Towards a Transnational History of Colonial Culture,” in Disputed Facts: Histories for the New Century, ed. Brian Moloughney and Tony Ballantyne (Dunedin: University of Otago Press, 2006), pp.65–92.

54 The most sophisticated recent historiographical treatment of trends in New Zealand art is: Francis Pound, The Invention of New Zealand Art and National Identity, 1930-1970 (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2009). On collecting, see Conal McCarthy, Exhibiting Māori: A History of Colonial Cultures of Display (Oxford & New York: Berg, 2007; Wellington: Te Papa Press, 2007).

55 David Bell, “Framing the Land in Japan and New Zealand,” Journal of New Zealand Studies 15 (2008): 60–73; Bell, “Ukiyo-e in New Zealand,” New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies, 10.1 (2008): 28-53. Richard Bullen, with David Bell, Geraldine Lummis and Rachel Payne, Pleasure and Play in Edo Japan (Christchurch: Canterbury Museum; University of Canterbury, 2009); James Beattie, “Japan-New Zealand Cultural Contacts, 1880s–1920,” in 63 Chapters to Know New Zealand, ed. Machiko Aoyagi (Tokyo: Akashi Shoten, 2008), pp.271–74. On the lack of scholarship on Chinese art in New Zealand, see Pound, The Invention of New Zealand Art, p.xiv.

56 Duncan Campbell, “What lies beneath those strange rich surfaces?: Chinoiserie in Thorndon,” in East by South: China in the Australasian Imagination, ed. Charles Ferrall, Paul Millar and Keren Smith (Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2005), p.173.

57 Pound, Invention of New Zealand Art, quote 9. An exception is: Anne Kirker’s thoughtful article, “T.A. McCormack: A New Talent to Emerge in the Nineteen-Thirties,” Art in New Zealand, 27 (Winter, 1983): 34–9.

58 While Japanese goods were more popular, Chinese objects also circulated in New Zealand. Campbell, “What lies beneath,” pp.173–89, for an account of the influence of Chinoiserie on New Zealand domestic interiors. On Chinese silks, note: WB Montgomery, Secretary of Customs, Wellington, BBAO, 5544, Box 1341, record 1912/412, National Archives (NA), Auckland; Alexander Rose, Collector and Registrar, Auckland—Chinese Silk, forwarding samples—opinion of GV Shannon, 1902, BBAO, 5544, Box 212a, record 1902/1118, NA.

59 “Chinese Art- Exhibition in New Zealand- Loans from British Collectors,” The Times, 5 August 1936.

60 “Humphreys-Davies”, AV2.6.136 H 1937, Auckland Museum; “Humphreys-Davies Collector File”, 0434 H01, Auckland Museum; “Ethnology: Chinse Art Exhibition 1937”, 1936-1939, MU000002/063/0007, alternate number 19/0/2, Te Papa Tongarewa – The National Museum of New Zealand, Wellington; ‘Ethnology: Chinese Art Exhibition 1937’, 1938-1960, MU000002/063/0006, alternate number 19/0/1, Te Papa Tongarewa – The National Museum of New Zealand, Wellington; “Chinese Art Exhibition and Collection”, 1937–1938, MU000216/001/0012, alternate number 19/0/1, Te Papa Tongarewa – The National Museum of New Zealand, Wellington”.